It’s a sad truth that tens of millions of people in the United States depend on free food to keep their families from going hungry. Many of these moms and dads plant and harvest fruits and vegetables or raise and package chicken and other meats, all for the lowest possible wage. As a result, the rest of us can spend less of our income on food than just about any other country on earth. Another result? Many farmworkers are too poor to feed themselves.

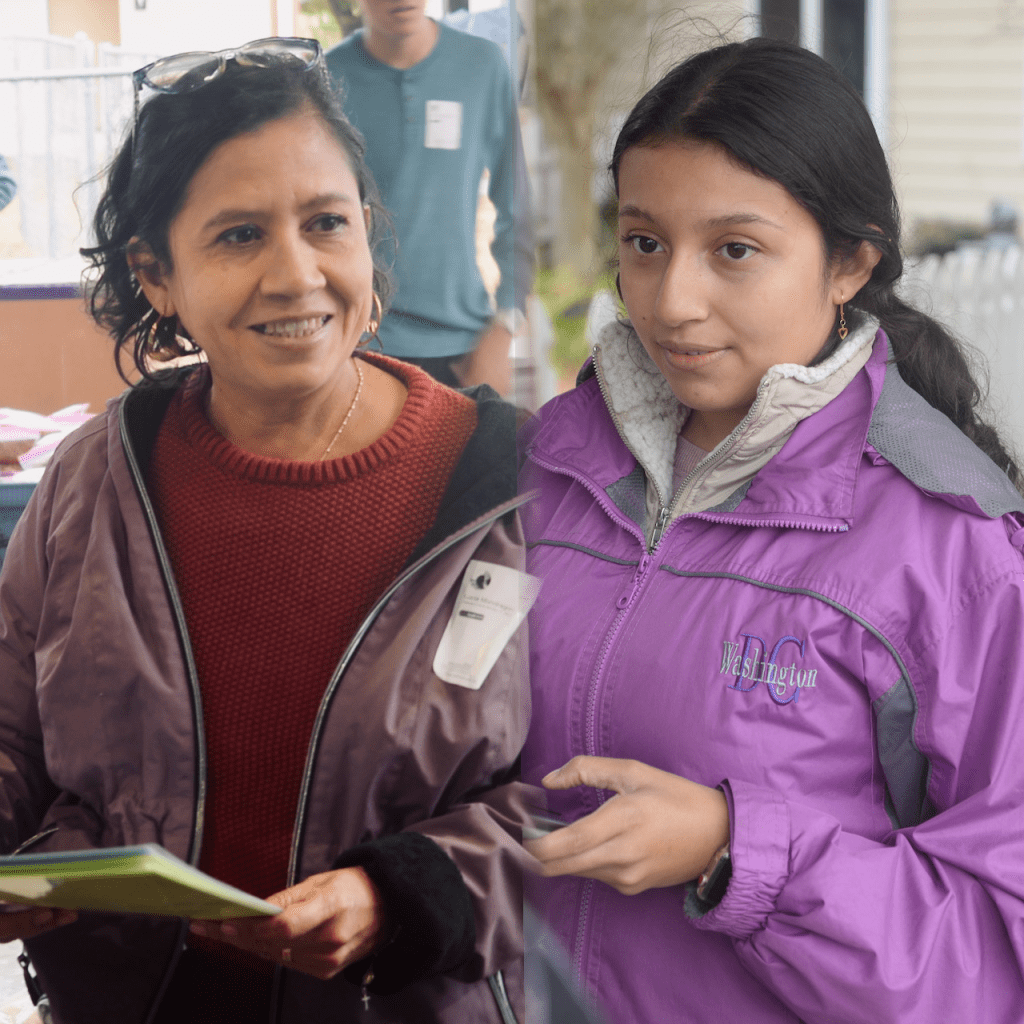

Fortunately for some, a little-known place in Sampson County has been helping to feed farmworkers and their families for more than forty years. The Episcopal Farmworker Ministry is located in the heart of this state’s farm country on a street named Easy—a misnomer if ever there was one. Just ask the people responsible nowadays for events like this one: Patti Navarro, Linda Reyes, and Anna Reyes are on the ministry staff. Fred Clarkson is the parish priest at La Sagrada Familia, an Episcopal church that shares the Easy Street campus with the ministry. Together, this team of four does work here that is anything but easy.

Patti Navarro first came here as a seven-year-old child of farmworkers, playing on the ministry playground while her mom picked up food for the family. Or some donated clothing. That was twenty years ago. Now she works here, collecting food items and helping to supervise the same food distributions that once kept her from going to bed hungry. She brings more than a firsthand appreciation for what it’s like to grow up in a farmworker family, and more than bilingual fluency. Patti possesses the ability to stay cool when things go wrong. And things always go wrong.

Pulling off a food distribution entails not one job but four. The first is advertising, to let families know when and where they can collect food. This job belongs to Linda Reyes. She relies chiefly on a Spanish-language Facebook page (they also have one in English) to get word out to their clients. It’s a well-known source of information for this community, and Linda posts here all the time.

Like Patti, Linda can relate personally to the community served here. Until a few years ago, she worked in a nearby pork processing plant until a ten-pound meat hook fell on her shoulder and sent her home, not gravely injured but frightened at what might happen next. She had been attending and volunteering at La Sagrada Familia (The Sacred Family) when offered this job. She jumped at the chance.

For this distribution, the last before Thanksgiving, Linda posts something new on Facebook: a signup form where families can register to get a free turkey, a ham, or a pair of chickens. It’s a heartfelt gesture but introduces a challenge: Where will they get all this meat?

The second job is the collection of food. For this event, that part culimates the day before the event on a cool and blustery Friday. For years, the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina has been the chief provider of food to ministry distributions. Today, long-time food bank driver Manny navigates a giant box truck onto the ministry campus and unloads eleven pallets stacked high with seven types of vegetables, watermelons, bread, and soft drinks—six tons of food. Patti and ministry volunteer Ruperto Martinez also pick up a couple hundred loaves of donated bread from the Bread of Life Food Pantry in Raleigh, and ten giant bags of rice and beans from Sam’s Club in Goldsboro. Patti has only $500 to spend at Sam’s Club, so each family will be limited to just one bag of rice or one bag of beans. It saddens Patti to not offer both halves of the staple rice and beans dish, but there is only so much money and she is trusted to spend it wisely.

“It’s kinda my job,” she tells me.

One reason Patti can only give rice or beans is that she had already spent $4,000 on 40 hams, 60 turkeys, and 204 chickens from the food service distributor US Foods. Those arrived first thing Friday morning. Patti had them loaded into the ministry’s aging walk-in cooler, careful to place them away from the constant drip of water from the ceiling. Will these three hundred pieces of meat be enough? Patti is doubtful. She calls the food bank to see if they might provide additional meat—she and Ruperto are willing to drive there to pick it up. Yes, she is told by the food bank rep who picks up the phone. Partner organizations can go to the Raleigh distribution center to pick up donated meat. Patti is ecstatic, but only until the rep asks for the ministry’s partner ID number. Patti doesn’t have it. She’s never needed it during the eight months she’s been at the ministry. So much for that source. The boxes of meat in the drippy cooler will have to do.

On the Friday before the distribution, while Patti oversees the collection of food, Linda guides a small team of volunteers in retrieving clothing from a double-wide trailer so they can distribute that on Saturday as well. Among her other responsibilities, Linda manages this oldest ministry program. In 1978, a group of parishioners launched what was then called the Clothing Closet Ministry, distributing donated clothing from a trailer just up the street from the ministry’s current home.

Job number three is the enlistment of volunteers for distribution day. It’s a difficult one. Being an hour’s drive from Raleigh, and three hours from Charlotte, the ministry’s remote location has always made this a challenge. As a joint operation of two of the state’s three Episcopal dioceses, the ministry can and does attract volunteers from a number of member churches. Indeed, parishioners of both St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Cary, and Trinity Episcopal Church in Fuqua-Varina, sign up to work at this distribution. But most of the 39 volunteers who show up are members of the very community the ministry serves—seasonal crop workers and meat production workers—many of whom are members of La Sagrada Familia, whose brand-new church building, just off the ministry parking lot, is now framed and clad in plywood. Linda is responsible for enlisting volunteers, but she gets some help.

Fred Clarkson, a native of Colombia, has been the parish priest at La Sagrada Familia since 2017. Earlier this year, he took on responsibility for overseeing all ministry programs, effectively forming a joint operation between the ministry and the church. Previously, the ministry had operated like an independent non-profit, sharing space with the church but having its own program and much larger staff. The consolidation has greatly reduced the ministry staff to just Patti, Linda, and Anna—in recent years the staff was more than double that size. But Fred doesn’t mind.

“The healthiest churches have the smallest staffs,” he told me.

With his own small staff, to make these food distributions succeed, Fred knows he has to do more than just help recruit volunteers from his congregation. A few months ago, Fred developed an all-new system, complete with an iPad face-recognition app, for registering food distribution clients and volunteers. It also prints out adhesive name tags for volunteers, to help distinguish them from clients. On the morning of a distribution, it’s Anna’s job to use this app, greeting each volunteer, asking them to look into the camera, then giving them a name tag. Once clients start arriving, Fred and Anna both handle registration.

Once you’ve advertised an event like this, and gathered the food and enlisted the volunteers, you are still left with the fourth job: orchestration. On distribution day, how exactly does all that food get into all those cars? What exactly should everyone do? And when? On the Saturday morning of the food distribution, as the team arrives, they can picture how all of this should work:

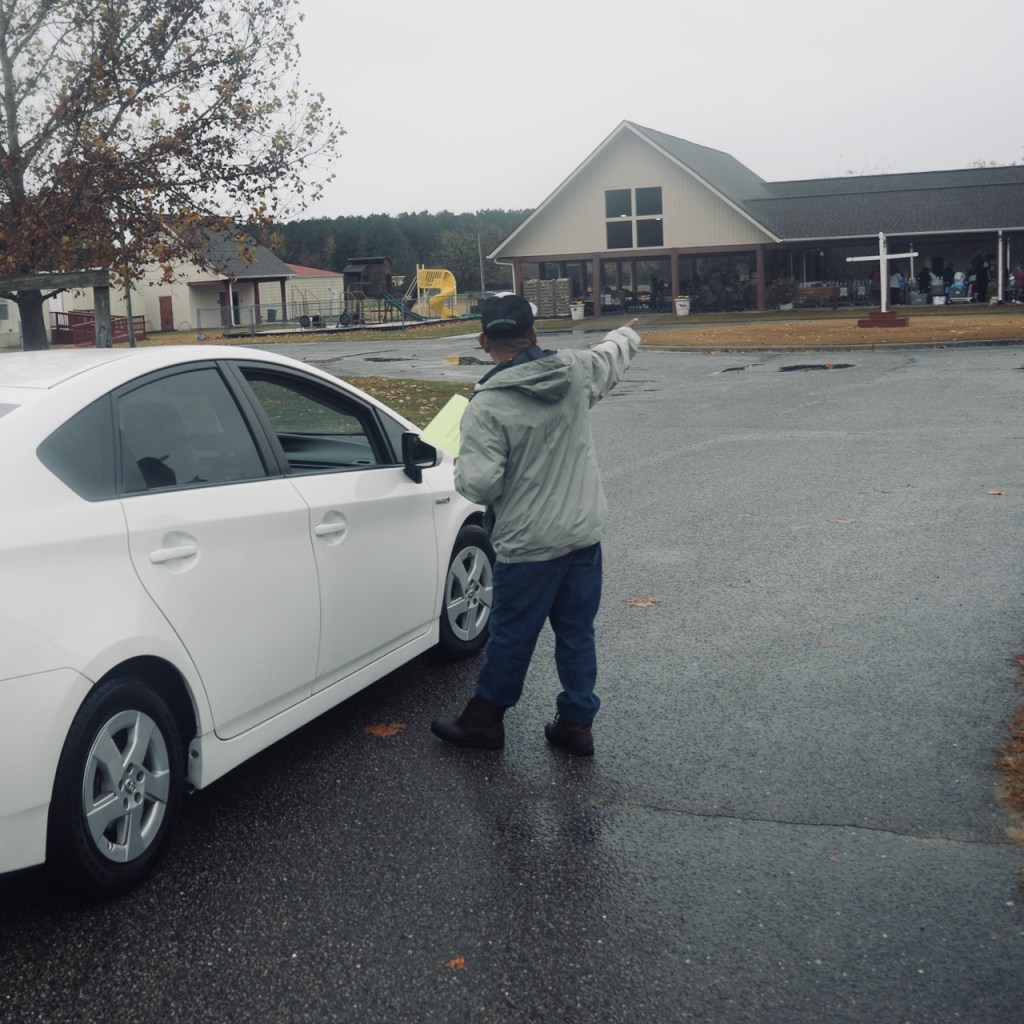

From 8:30 to 10:00, after checking in with Anna and donning a name tag, volunteers will unwrap eleven pallets of donated food, load bulk items like apples and onions into smaller bags, and then place it all out on tables—one for each type of food. There are also two-way radios to clip on belts (Anna takes care of this), take-home boxes to assemble, and shopping carts to roll out. Normally, clients roll these from table to table and gather what items they want. But the team will today introduce a small refinement to help speed things up: they will ask volunteers to pre-load boxes with several items and place those into the carts. While all this is going on, clients arriving in cars will be greeted at the entrance of the parking lot, handed a laminated card with a number on it (indicating their place in line once the distribution begins) and then directed to the soccer field behind the main ministry building. There, a volunteer will organize them into neat lines of ten cars each.

From 10:00 to 1:00, as the plan goes, Patti or Anna will use their radio to call out to the soccer field for batches of cars, ten each, to be sent forward. Clients will then move their cars to the ministry’s south parking lot, which has been cleared of all ministry and volunteer vehicles, then walk to the registration table. While waiting to register, clients can look through bins of donated clothing and bed sheets for whatever they might need. Once registered, clients take one of the pre-loaded carts of food and roll it to the meat distribution table. There, Patti will ask the client’s name, look it up on her laptop, then hand out whatever type of meat they registered for: a turkey, a ham, or two chickens. If someone has not registered, they still get chicken. But only one. Their shopping carts full, clients roll them to their car and unload them. When about half the cars have departed, the call goes out by radio to the soccer field for another batch of cars. Cleanup begins once the last car departs, after which everyone goes home.

That’s the plan. And things do, in fact, go generally according to plan. But not entirely.

It’s 49 degrees and drizzling when the team arrives a little after 8am. The high today is only forecast to be in the fifties, but thankfully the rain is supposed to end in about an hour. By 8:45, almost 20 volunteers are busy putting out loaves of bread, watermelons, and cabbages. Others are putting bulk items like carrots and apples into smaller bags. Fortunately, most of these volunteers have been here before and need only be assigned a station. Once everyone has a task, Patti rolls out a large speaker, turns on some music, and cranks up the volume. The opening lyrics of Luis Fonsi’s Despacito are just filling the open-aired workspace when Patti realizes some of the volunteers brought children with them. She quickly changes the music to De Música Ligera by Soda Stereo. Someone asks Patti why she didn’t like the first song. “Not PG-13!” she answers.

Patti is in constant motion. She checks to see if everything has been taken out of the cooler, from the van with donated bread, and the warehouse everyone calls la bodega. She answers non-stop questions. And at each station she does some math, determining how many of each item will go into a shopping cart. Watermelons are easy: one per family. For things like onions and cucumbers, she must estimate how many there are and divide by 300—the most families she expects. She need not estimate at the massive carton of soft drinks, whose content count is written on a label.

“783 divided by 300,” she says outloud, tapping into her iPhone’s calculator. “Three apiece. Wait. We need these for the Christmas party,” she concludes, before asking a volunteer who knows how to operate a pallet jack to move the sodas to la bodega.

Her main job now is to direct people and solve problems, like one at the meat station. At last month’s distribution, each chicken came packed in its own bag. Here, there are six chickens per bag. Volunteer Barbara Lawrence asks Patti if there are latex gloves and smaller bags. “Yes!” she answers, returning in no time with both. She isn’t sure the ziploc bags are big enough, so puts on a pair of gloves and bags the first chicken herself. The bags are just big enough. Patti takes off the gloves and dashes off to where she’s needed next.

Whoever designed this multipurpose space might’ve had events like this in mind. The 200 or so square foot area features a smooth concrete floor, a soaring cathedral ceiling, and no walls—just pillars. This allows for the constant and easy entrance and exit of people at nearly any point, as when Patti exits between two pillars, into the persistent drizzle of rain, to be sure arriving cars are properly greeted and instructed. She’s especially concerned that each client family gets only one of the pre-numbered cards, which will act as their entrance ticket at the registration table. Her mind is soon at ease.

Longtime volunteer Ruperto greets each family at the entrance of the parking lot, hands them one card, and directs them to the soccer field where raincoated volunteer Shirley Lamont forms lines of ten cars each. By 9:15, the first line is full. Shirley attends Trinity Episcopal Church and has been volunteering at these events for eight years, often accompanied by her husband Alex, who at this moment is loading shopping carts with cardboard boxes. Ruperto has been volunteering at ministry events for even longer. He works the night shift at a nearby turkey farm, so typically arrives to work these events having been awake all night. “Trabajaste anoche?” someone asks him this morning. Did you work last night? No, he answers. It was Friday, his night off. When he came here yesterday, to help gather food, he had been up all night working.

At 10:00, when the distribution is scheduled to begin, the drizzling rain shows no sign of letting up. With winds picking up, the effective temperature is dropping. There are 95 cars lined up in the soccer field, their occupants hoping to turn on their engines at any moment. But over in the distribution area, things are nowhere close to being ready. There’s just too much food—more than 20 thousand items—to be bagged and set out in the 90 minutes alotted, despite arms flying nonstop and everyone working at top speed. And some volunteers arrived just minutes before the scheduled start of the distribution. Half an hour later, the team decides things are ready enough. She turns off the music and speaks through a microphone to finalize station instructions, pointing to each table and confirming who will be sure its table remains loaded with food.

“Maria en la zanahoria, Enrique en la repollo, Alex en la sandia,” she calls out before switching to English. “Who can give out hand sanitizer? Who can retrieve empty carts?” English-speaking volunteers raise their hands.

Satisfied that all bases are covered, Patti tells volunteers they can go through the line now to collect a despensa for their own family. It’s the Spanish word for pantry, which in Anglo cultures generally refers to a room or cupboard, but in Latin American cultures refers simply to a load or collection of groceries. Most of the volunteers here need a despensa as much as those waiting in cars do. By showing up early and helping to prepare them, they can be sure to get one before food runs out, as it does more often than not.

At 10:45, everything is finally in place and the team is ready to receive clients waiting in the soccer field. Patti uses her two-way radio to ask Shirley to send out the first batch of cars. There is no answer. She presses the talk button and asks again. Still no answer. Patti disappears into the rain, running out to the soccer field to tell Shirley in person. Ten minutes later, clients are wheeling shopping carts full of groceries out to their cars. Ten minutes after that, Anna uses her radio to call out. “Shirley! Send another ten!” This time Shirley responds. The great transferance of food to families is finally underway.

Many of the recipients of today’s food are cropworkers. I wonder what they think as they eye the very type of produce they plant, cultivate, and harvest in their jobs. One crop they will never see here is state’s number one crop. North Carolina produces more tobacco than anything else—as has been true for four hundreds of years—and far more than another other state. The second leading crop is sweet potato, which is often a feature of ministry food distributions but not this one—perhaps because growers sell so much of it for Thanksgiving there isn’t much to give away right now. But on these tables today the crop workers do see watermelons, cabbages, onions, cucumbers, and zucchini. And those are all grown in abundance around here. The meat production workers here are certainly familiar with the meat items going into these carts. Each year, North Carolina raises, slaughters, and packages these in staggering numbers: 8 million hogs, 28 million turkeys, and nearly one billion chickens—more than 2 million a day.

The explosive growth of this state’s meat production in recent years has altered the very meaning of the term farmworker. It once referred to crop workers but is now practically understood to include meat production workers as well. Like virtually all crop workers, the men and women who actually raise, slaughter, and package all those animals are nearly all Latino, all generally paid the lowest wages that federal law will allow. Meat production workers tend to live here year-round. Some crop workers do as well—they are known as seasonal workers. But a large number of crop workers migrate here each year from Mexico by way of the H-2A visa program, living for the better part of every year in one North Carolina’s two thousand or so labor camps. A smaller number of workers migrate domestically, typically harvesting citrus in Florida during winter months and other crops in North Carolina and other more northern states during warmer months.

Of course, one need not be a farmworker of any kind to receive food at a ministry food distribution. You need only be willing to give your name and county you live in, get your photo taken, and wait in line. There’s a family who lives right across the street from the ministry, at a house where I’ve seen a Confederate flag atop a pole in their yard. I’m told they’ve been here for food.

By 11:30, only 20 cars have left the soccer field. There are more than 100 still there. The holdup is at the meat pickup station. There, Patti must ask each family for their name and look them up on her laptop, to see what meat they pre-ordered. That process stops entirely when she is called away to fix new problems, such as when they run out of ziploc bags for the chickens. Fortunately she finds a new box of bags, far larger than necessary but adequate for the job.

There are issues at the registration table, such as when a family shows up without a numbered card. They did not know they needed one. Father Fred explains the process then sends them back to their car, pointing toward the soccer field where they can join the end of the line to wait their turn for a despensa. The energetic son of a volunteer, too young to work but paying keen attention, notices Fred sending the disappointed family away. Fred notices the boy staring up at him. “We have to be fair,” he explains.

At 12:30, a family with card #98 signs in. Patti has sped things up at the meat station, such that 80 families have been served in just one hour. Things are picking up. So too is the wind. People are shivering now so Fred asks a volunteer to retrieve three propane-powered space heater from la bodega, the kind restaurants use for outdoor seating areas. In the open-air space, they provide heat in only three tiny areas. But at least it’s a place people can go to for a break of warmth.

Out in the soccer field, Shirley tries to keep moving to stave off the chill of standing so long in the drizzly cold. At one point she has an opportunity to run into the covered workspace, to find her husband Alex. A car won’t start. Apparently, its battery is dead. Alex uses jumper cables to get it going. An hour later, another car’s battery is working but the engine won’t turn over. Shirley thinks the engine is flooded and advises the driver to sit and wait. Later, someone’s car alarm goes off at the end of the line. Too tired to investigate, she lets it wail.

At 1:30, a half hour after the scheduled end of the event, nearly 30 cars remain in the soccer field. Inside the distribution area, fatigue is setting in. Staff and volunteers say little. The music blasting from the loudspeaker does not help. The Girl from Iponema, with its smoky bassa nova beat and minor key melody, only adds to the downbeat vibe. But not everyone is sullen. Outside, the rain has finally stopped, and half a dozen kids, from toddlers to pre-teens, are all over the slides and swings in the playground area, dashing about in glee as kids on playgrounds do.

By 2:30 the rain is back. The playground is again empty. But minutes later, Patti picks up the microphone to announce the last of the cars have left the soccer field. Fifteen minutes later, those familes have driven off with their groceries and cleanup begins.

Two hours later, the team goes home after an intense eight-hour day at work. They think of what to fix next time. First, the pre-loaded carts will go. Families, unsure how much they could take, ended up helping themselves to more food items from the tables. Next time, they’ll put out instructions on each table with the number of items alotted to each family. Linda will also think of how to better advertise the event to more families not on Facebook. And of course Patti will use the ministry’s partner ID number to secure meat products from the Food Bank, saving some of the ministry’s precious cash.

The team is especially relieved that the meat they bought was enough. Not only did every family get a turkey, ham, or chicken, but nearly 30 pieces of meat remain in the cooler, along with several bags of carrots and onions. Everything else is gone. But at least they will have food to hand out for the next few weeks. Farmworker families arrive nearly every day of the week at the ministry, to ask for help of one kind or another. When the help they need includes feeding their families, Patti or Linda or Anna can walk them to the cooler for a despensa to take home.

This little-known ministry on Easy Street has been serving this little-known community of agricultural workers since the 1978 launch of the Clothing Closet Ministry. A few years later, after expanding their programs to include food distribution and other services, the name changed to the Episcopal Migrant Ministry. It took its current name in 1986. Since then, the structure and leadership of the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry has changed many times. Running a place like this entails any number of challenges and periodic reinvention is inevitable.

The people here—the members of the board, the leadership, the staff—they all come and go. Sometimes those transitions are difficult. But the essence of this place, its spirit if you prefer, never seems to change. Nor does the simple reason why people show up here to work or volunteer: They are here to address the poignant and stubborn truth that among the hungriest in this country are those who feed the rest of us.

Photos by Michael Durbin