After graduating from East St. Louis High School, James Kalish remained determined to be a history professor as he excelled in college. On one of his visits home from Northeast Missouri State Teachers College in Kirksville, Missouri, in 1933, he met a delicate young woman named Bernice Malec at a dance. She accepted the impeccably fit college man’s offer of a date, but may have disregarded her mother’s advice about mixing men with beer. In any event, James soon learned his girlfriend was expecting his child.

As much as he valued education, James valued commitment to family even more. So he gave up his dreams of a college degree and teaching career and got a job hauling salt at the Swift meatpacking house.

Fortunately, he owned a place with plenty of room for him and Bernice to live. Unfortunately, it was the Savoy Hotel. That’s where they were living when their daughter Lorraine was born in December 1933.

“For our first home we lived in an apartment,” Bernice would later tell granddaughter Ann Mahoney, “above a cathouse.”

As one might expect, Adam and Julia Malec didn’t like the idea of their daughter and granddaughter living in the red-light district—especially when they learned another grandchild was on the way. A small rental house they owned next to their own on 8th Street was vacant.

Shortly after Lorraine’s sister Jackie was born in 1935, James and Bernice moved their young family into 1119 8th Street. James and Bernice slept in a rollaway in the kitchen, and Lorraine and Jackie shared the bedroom. And that was the entire house.

For bathing, when weather permitted, they filled a tub on the back porch. Otherwise, they washed as best they could in the kitchen sink. There were no closets, and when nature called there was an outhouse in the backyard—a two-seater, with one hole sized for adults and a smaller one for kids.

The family did have a car. To give Bernice a break, James would take the girls along when running errands, including trips to the Savoy Hotel to collect money from his Uncle Joe—before he drank it.

On one of those trips, after dark, James locked the car and instructed the girls to wait. Soon came the beam of a flashlight, in the hands of an East St. Louis beat cop, who tapped on the glass and asked the little girls what they were doing.

“Who are you?” asked Jackie, all of five or six years old.

“I’m a policeman,” he said.

“Show me your badge!”

And he did—just before James emerged from the Savoy, hurrying over to make sure everything was all right. The cop said it was—but instructed James never again to bring his girls back to the Valley.

In 1941, they moved to a house James built, with the help of friends, on weekends, at 5607 Lake Drive on property he had inherited from his dad. He got help from friends he had ridden the trains with to college in Kirksville and salvaged wood from buildings being demolished in St. Louis. This house featured indoor plumbing. They were living there when, in 1943, Bernice gave birth to son James R. Kalish.

For the thirty-one-year-old James, life up to this point had been pretty rough more often than not. Now, at long last—living in a house on Lake Drive, with a beautiful young family—life was pretty good. And it would stay that way.

Mom and her sister Jackie and brother Jim got good educations at well-equipped schools, spent free time in the giant sand-bottomed swimming pool at Jones Park—said to be the largest inland beach of its kind in America—and took summer “vacations” at Grandma and Grandpa Malec’s house on 8th Street, where they were showered with attention.

The girls were occasionally put to work, once sent to the corner tavern on Exchange Street behind the Kassly funeral home with an empty bucket to be filled with beer. The tavern keeper obliged, but they found it difficult to keep things steady on the walk home. They spilled so much beer they were never given that chore again.

Most Sundays for the young Kalish family included a suppertime visit to Grandma and Grandpa Malec’s house. During one of these visits, on December 7, 1941, they listened to radio reports of an attack on U.S. ships by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The U.S. entered World War II the next day.

Unlike later wars, this one was felt by virtually every household in America due to the rationing of everyday goods. Shoes, for example, were limited to one pair per year. Grandpa Malec used his skills from his cobbler days in Hamburg, Germany, and his handy shoe lasts, to keep everyone’s shoes in good repair.

The Kalish family could at least count on meat on their table nearly every day. The packing houses let workers buy meat at a discount, and James took full advantage. He’d bring home whatever cut was available that day—short ribs, organ meats, pig knuckles—but never hot dogs. Nor bologna or liverwurst, known then as Braunschweiger.

James had sworn off processed meat of any kind after one day in 1940 watching a coworker sweep the grimy packinghouse floor and empty his pan into one of the grinding vats. This was where, he learned, they always deposited whatever could be swept off the floor. As he peered into the machinery that day, he spotted among the soiled, boot-trodden meat scraps a campaign button. “Wendell Willkie for President,” it read.

The powerful grinders reduced the visage of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s dark-horse opponent to tiny flecks of filler, and James could only imagine what else might be going into America’s wieners and franks.

James sold the Savoy Hotel in the 1940s to a woman named Polly. His timing was unfortunate. The hotel was bought by the state just a few years later when it had to be demolished to make way for the Veterans (later MLK) bridge and interstate highway. The new owner no doubt made a handsome profit from its condemnation.

James and Bernice provided many things to their children, but ethnic identity was not one of them. Like many children of immigrants, they took pains to break ties to the old country. They didn’t want to be seen as immigrants—especially during wartime. They were Americans and felt obligated to reinforce that.

They spoke only English at home and discouraged their children from learning any Slovak or Polish—languages James and Bernice knew well. And garlic was allowed only on Sundays at family gatherings—God forbid coworkers or schoolmates catch a whiff and mistake them for immigrants.

The Kalish kids all did well in school. Lorraine went to Sacred Heart for two years, then Morrison Grade School through sixth grade, then Clark Junior High, and finally East St. Louis High School. There, she applied for and won two college scholarships.

One thing James and Bernice did pass down from earlier generations was an unbending work ethic. This was a working-class family to its genetic core, and every member knew that if you wanted something you worked for it. So when the kids became teenagers and wanted extra money, they got jobs.

Mom found a job—a fateful one, it would turn out—at Jimmy’s Malt Shop on State Street. There she met a sailor on leave from the U.S. Navy, Bill Durbin, looking for a date to an upcoming dance. They would marry and have ten children.

In 1961, after the kids had moved out, James and Bernice moved from Lake Drive to another East St. Louis house at 770 Pershing Street. In the 1970s, they moved out of ESL altogether, a few miles east to 24B S. Indiana Avenue in nearby Belleville, Illinois.

For decades, James and Bernice were regular visitors at family holiday dinners. Until 1973, when daughter Lorraine’s family moved to Washington, DC, all of their children and grandchildren were a short drive away.

Many of those grandchildren recall Grandma and Grandpa Kalish arriving in a modest sedan, with James in the driver’s seat and the passenger seat empty. Bernice sat in back—not out of haughtiness, but because James, safety-conscious in all things, refused to turn the key until anyone riding up front put on their seat belt or moved to the back. Bernice chose the back.

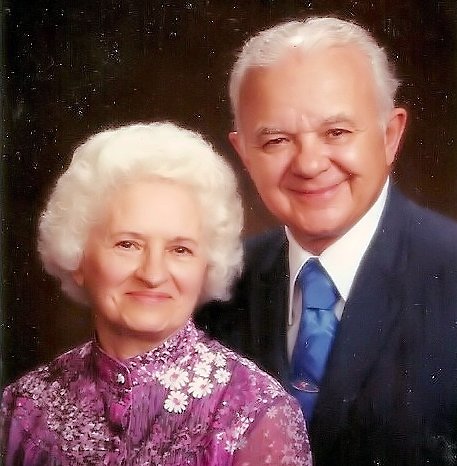

In 2004, Truman State University (as Northeast Missouri State Teachers College was then called) awarded James a certificate recognizing a life of encouraging education for his children and grandchildren. He and Bernice and all three of their children gathered at Fisher’s Restaurant in Belleville—a favorite—to celebrate.

Bernice died later that year, in September, at age ninety. She had lived long enough, she told her family, so she stopped taking her medicines and let nature take its course.

James died in October 2008 at age ninety-six, a few months after losing both legs to gangrene. His daughter Jackie brought a pair of his shoes to the memorial service and placed them at the foot of his casket.

In her eulogy, Jackie recounted a quotation she had learned from her dad as a young girl, after complaining about not having something—a piece of clothing, maybe, or jewelry—that her friends all had:

“I once cried for having no shoes,” her dad had recited to her, “until I met a man who had no feet.”

Next: 18. The Navy Years

Previous: 16. The Walko Family 1929-2003