Remarks at Nuevo Amanecer 2024 at the Kanuga Conference Center in Hendersonville, North Carolina

Good afternoon. My name is Michael Durbin.

For more than ten years I’ve been a volunteer at the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry in Dunn, North Carolina. Nowadays I am also the Outreach Coordinator for La Sagrada Familia, the parish church located on the EFM campus. I appreciate this opportunity share some of what I’ve learned, in hopes it might help others who want to help those who feed us.

Much of what I’ll share today is taken from a book I’m writing. It’s a narrative portrait of the farmworker community in North Carolina, based on interviews with workers, growers, legal advocates, camp inspectors, and plenty of others who know this world well. If you subscribe to my website at michaeldurbin.com I will send you an email as soon as it is available. I’ve also been blogging about farmworkers for a while now, so you’ll see plenty of blog posts there as well.

Imagine

To begin, imagine for a moment you are a healthy young man, a US citizen, with a wife and a child and a job that pays $15 per hour. It’s just enough to feed your family but not much else. Then you learn of a perfectly legal job that pays a remarkable $150 per hour. You are perfectly qualified. Would you take it?

Well, there’s a catch. First, you must leave your family for most of every year—they cannot come with you—to work in a foreign country where they speak a language you don’t know. You might live in a low-quality labor camp, and you may have to work very long hours in the hot sun with little or no breaks. Would you still take it?

Each year, hundreds of thousands of men in Mexico face this very choice. And they take these jobs, doing farmworker in US crop fields, authorized by an H-2A temporary, seasonal, agricultural work visa.

Why? The minimum hourly wage in Mexico is the equivalent of about $15. This year, the hourly wage for H-2A farmworkers in North Carolina is just under $16—per hour.

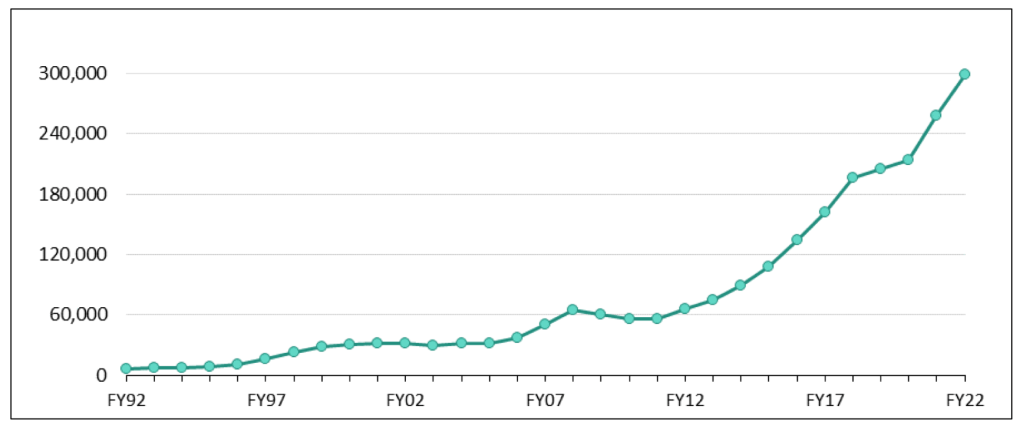

The number of men who takes these job is growing like crazy. Last year, 370 thousand H-2A visas were certified. That’s more than the population of Cleveland, Ohio. Soon, we can expect more than half a million Mexican men to each year leave their families for the better part of every year, enduring living and working conditions that few US citizens would ever tolerate. Many of these men will do this for the entirety of their adult lives.

Finding the ministry

I don’t know what it’s like to do farmwork. I’m a software engineering manager for the banking industry. Since 2013 I have been a volunteer at the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry.

It’s located in Sampson County, about five hours east of here, in the part of the state where most H-2A workers live and work.

One of the things that drew me to this place is the banner that used to greet visitors to its website. “Good knows they need our help. God knows we have it to give.” It struck me as beautiful. And clever. It still does.

Most of my volunteering has been to support the ministry’s outreach program where we visit migrant farmworkers in the labor camps where they live. My experience has taught me that—surprise, surprise—God is right! They do need our help. And we do have it to give.

This invisible world

Everyone in the United States eats food. And here we pay less for our food than in most other countries. But hardly anyone seems to know about the hundreds of thousands of workers, mostly men, who leave their families in Mexico for much of every year to plant, cultivate, and harvest our crops, ensuring their abundance.

Few people know that family separation is built right into this system. So is an imbalance of power one does not see in any other legitimate industry this country.

Our H-2A farmworkers must re-apply for their jobs every year. Desperate to keep them, they will tolerate living and working conditions that are not always, but certainly sometimes, abusive–all so the employer will ask them back. Growers say they can’t afford to make things any better for their workers. Farmworker advocates disagree. The debate rages on. Meanwhile, this army of homesick dads, separated from their families, grows and grows.

Our H-2A farmworkers are, sadly, following a tradition that stretches back hundreds of years. Like much of the US South, North Carolina’s agricultural economy has always depended on a steady supply of artificially low-cost labor. For more than two hundred years it was the enslaved man, woman, or child who did most of our farmwork. Then it was the tenant farmer and sharecropper—neither of those jobs was much better than slavery—then a Black or poor White US citizen migrating from state to state. Then, an undocumented farmworker from Mexico. Today, most of our farmworkers are Mexican men authorized to work here on a temporary seasonal non-immigrant H-2A visa. We call them guest workers.

The H-2A program

US growers can hire all the guest workers they need. There is no cap on this type of visa. But there are requirements.

Jobs must be offered to US workers (almost nobody takes them). You can see the job orders for these jobs at seasonaljobs.dol.gov. Employers must provide free housing, reimburse workers for travel, and pay a minimum hourly wage known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate, or AEWR: $15.81 in North Carolina this year. They must also provide work for at least 75% of a contract period. As we’ll see, this so-called “three-quarter rule” can be a problem.

The H-2A program began way back in 1986 as part of the Immigration Reform and Control Act, or IRCA, which also made it unlawful to hire undocumented workers. IRCA also provided a path to citizenship for millions of undocumented workers already here. And, it dusted off an old guest-worker program known as the H-2 to create H-2A for temporary agricultural workers and an H-2B program for non-agricultural workers.

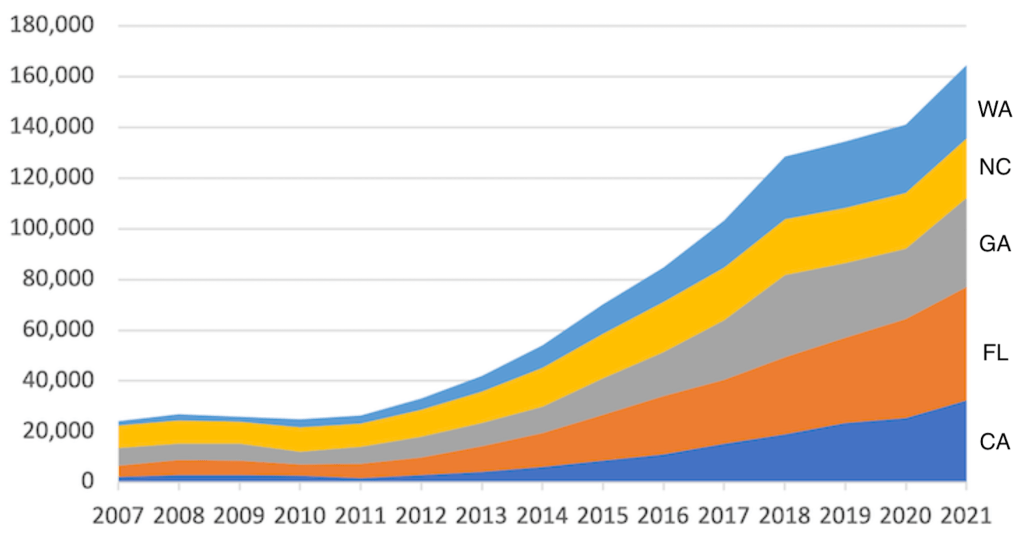

For many years, no state received more H-2A farmworkers than this one. Now, after a recent and dramatic growth spurt, a majority of H-2A farmworkers can be found across five states: California and Washington, Florida and Georgia, and North Carolina.

There are roughly twenty-five thousand H-2A farmworkers here. As in other states, they are not the only ones doing farmwork. Many so-called seasonal workers live here year round, and there are still traveling farmworkers who move around with the seasons, maybe picking oranges in Florida during the winter then moving up the coast to other states for the rest of the year. A number of seasonal and traveling farmworkers are undocumented, so it’s impossible to say precisely how many farmworkers there are. I think the total is around seventy-five thousand. Nearly every single one is Latino.

H-2A employers

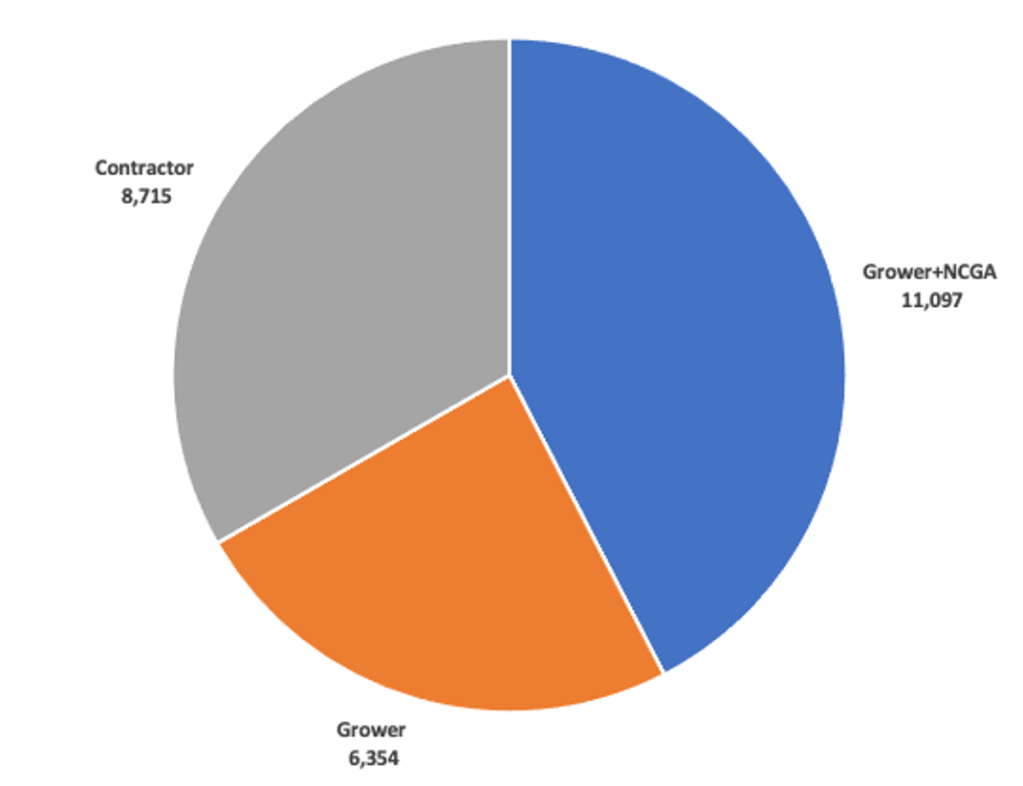

Each year in this state, nearly 1,000 employers sponsor H-2A visas. They fall into three categories. The first is the individual farming operation, or grower, hiring workers for their farm. There are around 200 of these. Another 700 are growers belonging to the North Carolina Growers Association, a trade association that acts as co-employer, filing paperwork and resolving issues for their members. The NCGA is the single largest H-2A employer in all the United States. The third type of H-2A employer is the farm labor contractor, or FLC, hired by a grower to take care of their labor needs. Fewer than 100 FLCs filed North Carolina job orders for 2022—barely 8% of all employers. But they hired a full 33% of the H-2A workers here. Nationally, their presence in the H-2A system is growing every year.

The birth of a ministry

There are a number of organizations across this state helping farmworkers. Of the ones I know about none has been doing this longer than the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry. In 1978, volunteers from a handful of churches began distributing clothing to migrant workers from a trailer. They quickly expanded their services, but there was a language problem. And the language was not Spanish. Many area farmworkers were then refugees from Haiti.

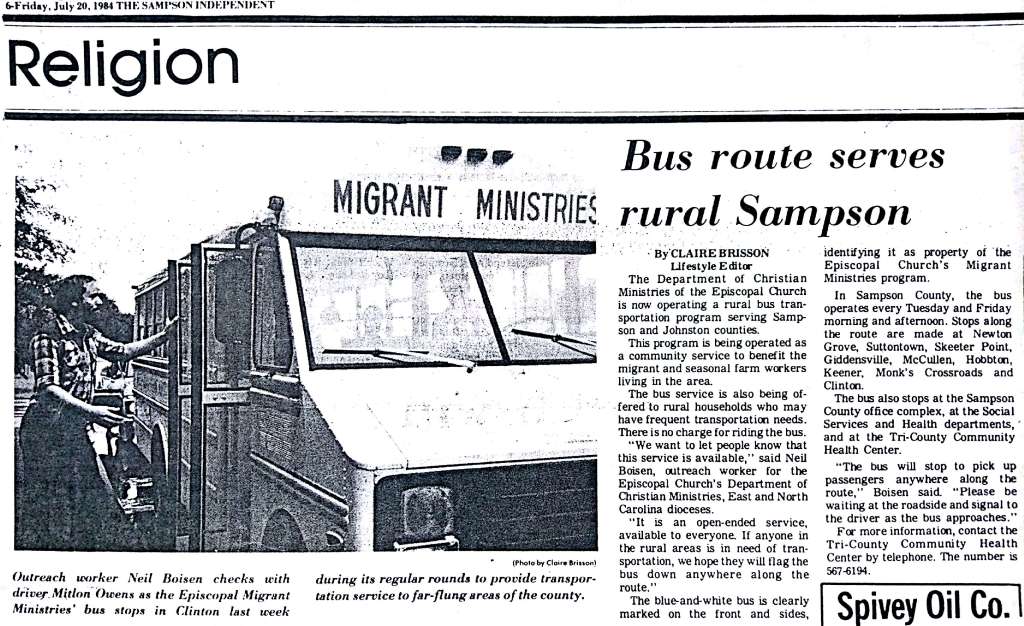

In 1982 the ministry hired their first outreach worker. Neil Boisen was a graduate student studying French at UNC Chapel Hill. He dropped out of school, went to camps with a Creole Bible, and sat with Haitian workers and asked them to read it to him. Soon he was soon speaking with workers in their own language.

Since Neil was here, the ministry has served hundreds of thousands of agricultural workers—both crop workers and meat processing workers.

Ironically, the ministry address, in the small town of Dunn, North Carolina, is 2928 Easy Street. The work there is anything but.

The Episcopal Farmworker Ministry is a joint project of two dioceses: The Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina, and the Episcopal Diocese of East Carolina. An East Carolina parish church, La Sagrada Familia, resides on its campus.

For more than twenty years, the venerable “Father Tony” Rojas ran both the ministry and the parish. Nowadays Father Fred Clarkson, who is with us at the conference today, has much the same dual role.

The ministry’s operating budget is small, but its spirited staff makes the best of every dollar. The range of ministry programs, past and present, is vast. It includes, or has included, Sunday services in Spanish, food and clothing distributions, immigration legal services, ESL classes, and disaster relief.

The EFM was a major vaccination site during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their white vans can be seen all over eastern North Carolina after every hurricane. Clothing distribution remains a mainstay program after 45 years, as does direct outreach to migrant workers at the labor camps where they live.

The camps

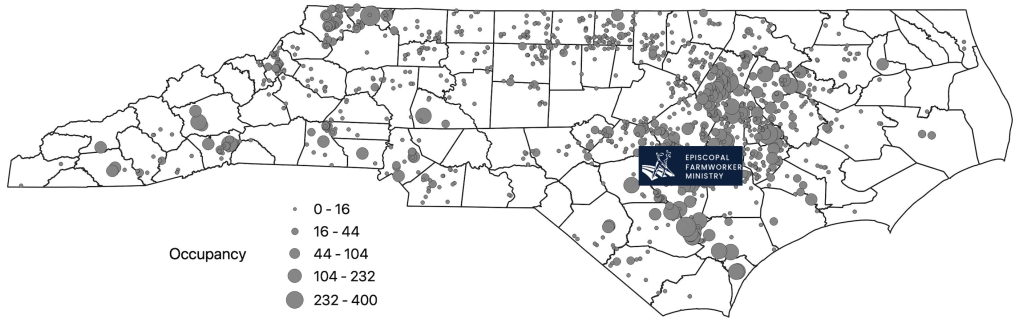

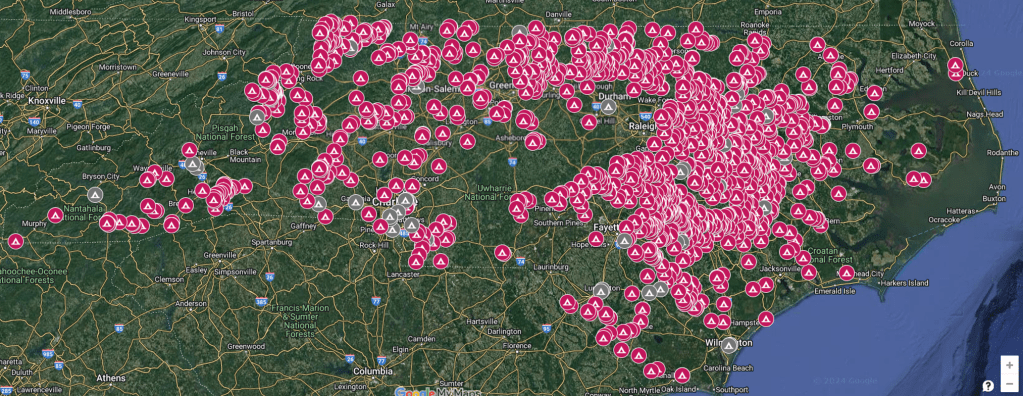

There are more than 2,000 migrant labor camps registered with the state. This is a Google Map I made after extracting housing site addresses from several hundred job orders for the 2022 growing season.

Camps vary greatly in size and structure. One camp might consist of a single trailer home for a handful of workers. Another might be an old farmhouse, or cinderblock barracks for two or three dozen workers. Another might be a sprawling compound of trailers and barracks where hundreds of workers live for months at a time.

State inspectors visit camps to ensure they meet health and safety standards. These standards are not very high. They do not require air conditioning—despite temperatures that can top 100 degrees. Nor do they require indoor plumbing—ancient outhouses, or privvies, are fine. I’ve seen many of those. Nor are washing machines required—a large bucket will suffice. State inspections are not perfect. As a result, some workers sleep on old mattresses with springs poking into their backs, or use broken toilets, or shiver in an unheated camp when temperatures dip into the thirties.

To be clear, not every H-2A labor camp in North Carolina is substandard. I’ve been to three camps here I would spend a night in myself. The other seventy or eighty I’ve personally been to? No thank you.

Let me also be clear on this: H-2A employers in this state, most of who are family-owned farms, are under extraordinary pressure to keep their costs down. Having to compete on price with foreign competition, and with no control over the price of all the things they need to produce a crop, it’s a miracle to me they can stay in business. Indeed, a number of North Carolina farmers go out of business every year. It’s little wonder why growers spend only what they must on the upkeep of their worker housing.

Finding camps

Before any aid organization can go to one of the almost 2,000 camps here, they first must first it. This is not always easy. Individuals who know where camps are come and go, and even a street address is not always helpful—some camps are hidden deep in the woods at the end of a road marked by no more than a No Trespassing sign.

This year, to help the ministry solve this problem once and for all, I tapped into my personal database of camp locations, extracted from job orders, and identified 100 camps nearest the ministry–each is less than a thirty minute drive from Easy Street. I put all these in a Google doc I share with the staff.

I gave each camp a unique name, then began visiting each one, usually with someone to help with the Spanish, to confirm its exact location. Then I put the GPS coordinates into the guide, so anyone can just tap and launch their driving instructions. We’ve been to 65 so far this year, and I’m determined to get us to every one by the end of the season.

I also include nicknames for the camps. This one, sadly, is known as the Prisoner of War camp because it looks just like one, complete with barbed wire fencing.

An opportunity

One time I was at a camp helping Margarita Vasquez, a very talented outreach worker who was once a farmworker herself—as a child. With their small hands, children are very good at picking berries, so that’s what she helped her parents do. On this day, Margarita was speaking with twenty or so workers at their camp when a white pickup truck arrived. The driver was the grower who owned this farm, a White man about my age. He eyed us with some suspicion, especially me, the only other Anglo there, and asked what we were doing. Margarita explained how we were there to provide safety information and clothing. He clearly did not like seeing strangers on his property. Then Margarita added that we were also inviting the men to celebrate the Holy Eucharist on Sundays. He thought about that, and then said, “Well, we all need Jesus Christ.” Then he pulled away. Margarita was smart to mention the church part last, so it could sink in some, but it also illustrates the unique opportunity for churches to help farmworkers. Unlike legal advocates and union organizers, who also visit camps, you are not a threat. You are there to provide aid to the workers they need.

What can a church provide to farmworkers? Clothing is always appreciated, as are towels and bedsheets—preferably not white, workers tell us. Hygiene kits are also always accepted. The EFM has volunteer events where they fill large bags with toothbrushes, toothpaste, deodorant, soap, and other such items. Information is always helpful, such as where workers can find local medical clinics. And some workers don’t know the address of their camp, which is essential if they ever need to call 911. You can of course provide information about your pastoral care and Sunday services, but you need to be ready when they ask you: Católico? I mentioned earlier that employers are only required to provide work for three quarters of a contract period. This means a worker here for eight months may go two months without work. If they send money home every week, which is common, then they will sometimes run out of money to buy food during these dry periods. So donated food items—tortillas, beans, and so on—can often keep a worker from going to bed hungry.

Personally, I think what workers appreciate most is simple recognition—a visit from someone who speaks Spanish—especially if they come back more than once. Doesn’t any person in need appreciate the another person who cares about them and takes the time to visit? With the explosion of the H-2A farmworker population, so grows the need to come to their aid—spiritual and otherwise. I think churches like all of yours are in beautiful position to do that.

A nearly impossible job

My time with the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry has been an incredible opportunity to meet some farmworkers and learn about their world. I have also learned how hard it is to do what they do over on Easy Street: Coordinating between two dioceses and among I don’t even know how many parish churches, recruiting staff, raising funds—there are endless reasons to simply give up. Our country’s deep political divide does not help. Depending on one’s party affiliation, different people have very different views on migrant farmworkers. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry saw this in 2014. He was then Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina and knew this ministry well. A journalist asked him about the mix of sacraments and social outreach offered here. He called it, “the work of Jesus that can be done by Republicans and Democrats.” I think an approach like that is more powerful today than ever.

I don’t have to tell anyone in this room how overwhelming it can feel to be in a position of service when so many are in need. I often feel that way about farmworkers. This year, of the 75 thousand agricultural workers in this state, the ministry will serve fewer than one thousand. Then I remember the starfish story. You probably know it. There are many versions but they all go something like this:

A man spots a little girl on a beach where a storm has washed up a countless number of starfish. The girl is picking them up and tossing them back into the sea, one-by-one, when the man says to her, “There are so many starfish! What you’re doing will not make a difference!” The girl tosses another one far out into the water and then says to the man, “Well, I made a difference to that one.”