Two weeks after his nineteenth birthday, in September 1948, Bill Durbin left East St. Louis on a train to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, about twenty miles north of Chicago, for basic training—aka boot camp. He wrote his first letter home within days of arrival and would pen hundreds more over the coming years (more than three hundred survive) to family and friends.

Bill took well to the heavy regimen of his new life and was even promoted to Company Clerk, a petty officer position, due to his year of college. He was happy with the Navy. “Gosh, but I sure like this kind of life,” he wrote home. “It seems to give one a feeling that every move he makes is a definite advancement toward an ultimate goal.” His pay was $75 per month—or $2.42 per day.

After three months of boot camp, he traveled by train to Norfolk, Virginia, where he was assigned to the USS President Adams, a troop transport. He applied for training as a radar operator, and after months of general duties on the deck crew, was elated in May 1949 to be formally assigned the role of radar operator on the bridge of the ship—a role he would fill for all his time in the Navy.

Over the next twelve months, Bill’s ship would make seven tours of the Caribbean, with stops in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Martinique, and Panama—places this young man from ESL had only read about. He found his first day at sea enthralling. “I’ve never seen such sights in my life,” he wrote. “The first morning at sea—sunrise! It’s magnificent! The sky is a million colors.”

There were other exhilarating experiences too, including his first bite of pizza on shore leave in Norfolk. He raved about the exotic new food in a letter home, complete with instructions on how to pronounce it: “PEET-zah.”

Not every letter was cheerful. His hours on duty could be punishing, such as the night he was woken from sleep to help repair mooring cables that had snapped. After repairing them in a freezing rain, the crew fell asleep, exhausted—only to be woken a few hours later to deal with another emergency. “I’ll never forget Dec. 25, 1948. Still want to join, Bob?” His brother Bob was in the process of joining the Navy too.

Bill had his share of seasickness but was proud to write of finding his “sea legs” in the middle of a hurricane, never getting seasick again. The homesickness, however, never went away. “I never felt bluer in my life than I do now,” he once wrote, urging his family to keep writing. He took solace too in his Catholic faith, attending Mass, receiving Communion, and making Confession at every opportunity. He never did anything to dishonor his family, he assured his mother near the end of his service. Apparently, he saw other sailors crossing lines he never would. He wrote to his dad that “the Navy might make a man out of you physically, but morally it wrecks you.”

The writing and reading of letters home helped stave off homesickness more than anything else. Most of his letters were with his mom and dad, but among his female pen pals were Margie, Dolores, Roberta, Florence, Phyllis, and a Gloria Simich—with whom a nascent romance, or at least a mutual crush, soon emerged.

In the spring of 1949, Bill requested leave in April so he could be home for Easter. It was denied. He submitted it again, and this time it was granted. But then he applied for an electronics training class, whose course work would conflict with leave. So he wrote his family—and Gloria—that he would not be home, directing them not to make plans to see him. Then, his application for the training class was denied. So he found himself home for Easter after all, but without a date for the Easter Dance, where George Stoltz and his orchestra would perform at the American Legion hall.

Determined to find a date, Bill went to his brother Bob for advice.

“Bill, I know the perfect girl,” offered his younger brother. “Lorraine Kalish. Works at the malt shop.”

A few days later, Bill approached the two-story red brick building on State Street, not far from the intersection with 29th Street where he lived, with its big electric sign marking the neighborhood institution: Jimmy’s Malt Shop.

“Are you Lorraine Kalish?” he asked, seeing the girl wiping the shop’s big picture window.

“You’re Bob Durbin’s brother,” answered Lorraine, catching the sharp-dressed sailor off guard.

Lorraine accepted the sailor’s invitation, enjoyed the dance, and accompanied Bill afterward to a roadhouse called the Chatterbox with a crowd of other couples. She didn’t enjoy that part of the evening as much, because she had never been around so many people drinking alcohol, which is not a surprise given her age.

Bob had failed to tell his brother that Lorraine Kalish was only fifteen years old, so Bill Durbin took her home to her parents and put her out of mind. He would find some other girl—an older girl—just as nice. Or so he thought.

After his leave, the letter-writing with Gloria resumed and things between them heated up. She sent Bill a three-by-six photo of herself that he tacked up on the bridge for other sailors to see, and he urged his mother to send a photo of herself to Gloria’s family, and to go meet them to introduce herself—both of which she did. He would tell his mother things “are very serious” with Gloria.

In September 1949, Bill’s parents shipped his accordion to Norfolk. It became his instant trademark among crewmates. Bill Durbin was a gifted musician who could play dozens of popular tunes, which at times he did for more than two hours a day. He drew crowds of twenty to thirty men whenever he picked up the bellowing and complicated instrument, and for the rest of his time in the Navy he was known as the accordion-playing radar operator.

In February 1950, Bill was transferred from Norfolk, Virginia, to San Francisco, California. The USS Adams traveled some eight thousand miles from the East Coast to the West by way of the Panama Canal. In San Francisco he attended several weeks of advanced radar training classes, where in May he finished with very high marks—ninety-eight percent.

In June 1950, Bill learned, along with everyone else, of a frightening development on the Korean peninsula. North Korea, with the apparent backing of China and Russia, had invaded South Korea in an attempt to spread Communist rule over all of Korea. With this, Bill’s non-combat tour of duty became a combat tour. The Korean War had begun.

Officially, the Korean War—as it was, and still is, known—was no war at all. The U.S. Congress never declared war on Korea. It was a “police action.” Still, we sent more than a million young men off to fight, many never to return.

In August, Bill crossed the Pacific aboard the decrepit USS Aiken Victory to meet up with the USS Eversole, where he would join his brother Bob, who was already on that ship in Japan. Bill knew the dramatically elevated stakes of this experience. Departing from San Francisco, he took one last look at the Golden Gate Bridge and wrote home, “I have a feeling of resignation that I’ll never see the U.S. again.”

The crossing took thirteen days, a journey he would later summarize as “a nightmare.” The ship did not need help with radar, so he was assigned to work as a cook, baking thousands of biscuits at a time. The aging ship was in bad repair, with few basic functions in working order. The worst came when they ran out of fresh water.

“We went without water all evening,” he wrote in his diary, “until my mouth was bone dry.” The food was so bad many sailors chose not to eat at all, to the point of experiencing early signs of starvation. “I’ve hardly eaten a thing the last two days—and I crave nothing,” he wrote. “A hard case of cramps just hit me, so I’m going to bed.”

In September 1950, the traumatic crossing behind him, Bill began serving on the USS Eversole as a radar operator on his first of two combat tours in Southeast Asia. His ship was based at various times in the Japanese port cities of Yokohama, Yokosuka, and Sasebo—about thirty miles from Nagasaki, where the U.S. had five years earlier dropped one of the atomic bombs that brought an end to World War II. During most of his combat duty, the Eversole was a member of Task Force 77, the celebrated aircraft carrier strike force in the U.S. Navy’s Seventh Fleet.

Two years into service, his opinion of the Navy had changed from what it was back in boot camp, when he liked it so much. “I get very little enjoyment out of the Navy,” he wrote home in late 1950. “I have one year to go and then I’m getting out and not going back.”

Weeks after writing those words, President Truman would only deepen that resignation with the declaration of a national emergency. Bill’s three-year enlistment was extended to four, and all members of the military were put on alert for full-scale war.

Engaged now in combat, the letters from home bolstered Bill’s spirit more than ever. He especially enjoyed letters from Gloria, until something changed. At some point they began diminishing his optimism for a long-term relationship. Her parents were not happy, she wrote, that she was involved with a man so far away. In the next letter she admitted that she too was having doubts. In the next, she warned Bill to keep his expectations low. There was no single so-called “Dear John” letter in this case, but rather a progression of them, each feeling like a bandage tearing slowly from his skin. One night in October 1950, his brother Bob ripped it off.

They had gone to their usual watering hole, a bar in Sasebo, Japan. Bill played the accordion, lifting his spirits only slightly. Later, his brother extracted from his pocket a newspaper clipping from back home, announcing Gloria’s engagement to another guy. Bill was not surprised, but he did know, once and for all, that if he were ever to experience romance, it would be with a different woman. The name of the Sasebo bar may have given him a clue: its name, incredible as it seems, was The Club Lorraine.

The name of the Sasebo bar may or may not have put Bill Durbin’s mind back on Lorraine Kalish. But something did. During his next leave, in April 1951, he went back to Jimmy’s Malt Shop and reintroduced himself. Lorraine, it seemed, was all but waiting. They saw each other every day of his leave. She even invited him to meet her parents at their house on Lake Drive, urging him to bring his accordion. There, he impressed James and Bernice Kalish with a casual recital featuring the jazz standard “Tiger Rag” and 1931 popular song “Lady of Spain.” It sealed the deal. These two were now an item, or “going with each other,” as was said in the 1950s.

Back in California after leave, his spirits lifted, he sat to write a letter to his new girlfriend—only then to realize he had failed to ask for her address. But he knew where she went to school.

So it was that one day at East St. Louis High School—or East Side, as everyone knew it—Lorraine Kalish was called from her classroom to the principal’s office. The exemplary student was baffled. Was she in trouble? No—it was only to retrieve the letter from Bill, but only after the office staff had passed it around for everyone to have a look at the racy USS Eversole decoration on the envelope, complete with a bare-breasted mermaid.

Bill and Lorraine agreed to write letters without waiting for replies before sending the next one. Lorraine found it nearly impossible to match the length of Bill’s long, daily letters, written in the finest penmanship she had ever seen. The lonesome sailor had so many experiences to write about, and she struggled to even fill a page, writing only on one side of the paper and in very large letters. This did not impress Bill.

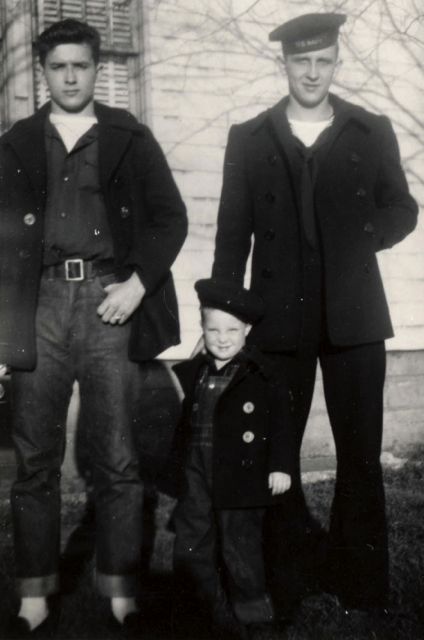

“My kid brother writes better than she does,” he wrote to his mother. “And she’s supposed to be a good student!” The “kid brother” was Richard Durbin, five years old at this time, who went by Joe Durbin in his youth, and later by Dick Durbin when he entered politics.

Most of Bill’s letters home ended with something like “Tell Joe to be a good boy” or “Tell Joe I enjoyed his letter.” Once he asked Joe to ask Sister Irmine, his teacher at St. Elizabeth’s, if she realized that fifteen years earlier, he himself had been in her classroom. Bill many times asked Joe to simply pray for him, as Bill did for him. “This can turn into risky business,” he wrote his little brother. “And I pray every night you’ll never see it.”

Meanwhile, on his second tour of combat duty aboard the USS Eversole, from the radar console in the CIC—or Combat Information Center—on the bridge (sailors joked that it stood for “Christ, I’m confused”), Bill Durbin supported shore bombardment, minesweeping (they would find and destroy three), and the rescue of other damaged ships. In one battle, the enemy lobbed twenty shells at his ship, none of them making contact. Another ship, filled with buddies he had trained and served with, was not so lucky. It was hit hard, and a number of his friends perished.

Bill Durbin was growing up fast. At the age of twenty he had to grapple with two possible futures: one in which he never made it home alive; and in the other, he settled down to married life. And more and more, he knew who he wanted to marry. In his letters he declared his full-throttled love to Lorraine, and she declared it right back.

In August 1951, a few days before his twenty-first birthday, Bill broke news of his love affair to his parents, with all the sincerity of a young man free of doubt that he had finally found his one true love, wrapped in playful giddiness:

Dear Mom:

Ah, love! It’s a fine birthday, it is, when the love-bug will take a big bite out of you. Yes, your son+heir has really fallen again, on firmer ground to be sure, this time. The apple of his eye is a sweet l’ill ol gal by [the] name of Lorraine. Ah, what a different, beautiful name it is! (I guess you think I’m nuts!).

But all horseplay aside, my interests are now centered on her. I had my doubts when I came off leave, so didn’t press it; in fact, I gave it every disadvantage to prevent a recurrence of my last “affaire l’amour.” But it has proven itself “thru trial and error.”

…

‘til next time

Bill

In her first letters, Lorraine’s writing skills had disappointed her Navy boyfriend, but that didn’t last long. He later wrote to his mother that Lorraine now wrote excellent letters, demonstrating an intelligence he admired as much as everything else about her. That intelligence had indeed earned Lorraine two college scholarships, leading to a period of uncertainty in the relationship: Would she go to college or marry Bill?

During his next leave, in April 1952, the question was settled when Bill and Lorraine announced their engagement on the day before Easter. The wedding date was set for the following April, 1953.

Bill had only five months remaining before his scheduled discharge from the Navy. He spent all of them in California, operating radar on countless “Hunter-Killer” training drills, preparing the crew for locating and destroying Russian submarines.

Letters during this time focused on wedding preparations, starting with rescheduling the ceremony for November 1952. Bill decided he couldn’t wait any longer than necessary and worried about being called back into service before the next April. In the heat of a war with no end in sight, and the very real possibility of it escalating into another world war, his concern was reasonable.

He bought wedding rings in San Diego, asked his best friend Joe Levy to be his best man, made a guest list with Lorraine, and counted down the days to his discharge. He expressed some reservation about leaving the service as so many new recruits were just pouring in, but ultimately decided he could be proud of his involuntarily extended service to his country. As things turned out, the Korean conflict came to an end nine months after his discharge, on June 23, with the signing of an armistice.

Bill would forever honor anyone who put their life at risk in service to this country, but his personal opinion of Navy life remained frank. In the last lines of his very last letter, demonstrating his talent with a pen, he complained about the food. “It’s time for me to go to supper,” he wrote. “I wonder what it is. I’ll still wonder after I eat it.”

Bill Durbin was honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy in San Diego, California, on August 23, 1952. He bought a plane ticket to get home as quickly as possible. At Lambert Field in St. Louis, he walked off the plane, beaming, into the arms of his mom, his dad, and his glowing fiancée.

Eight weeks later, on November 22, Bill Durbin and Lorraine Kalish were married at St. Patrick’s Church on Summit Avenue in East St. Louis. As they climbed into the back seat of the limo after exchanging vows, in front of a church packed with family and friends, the photographer snapped a photo of the two happiest newlyweds this world has ever seen.

They had seen each other for only a few weeks’ worth of leave time before announcing their engagement. But that was all either of them needed to believe this would be a loving, lasting, and all-around excellent marriage. Time would prove them right.

Next: 19. Ridge Avenue

Previous: 17. James & Bernice Kalish 1933-2008