The multi-family enterprise in Zeigler, Illinois was wildly successful. For a time, Prohibition was very good for this family, proving that entrepreneurs will always find ways to satisfy widespread demand for just about anything.

Louis earned enough money in Zeigler—from renting rooms, slinging drinks, and whatever else—to bring the operation back to East St. Louis. He moved back with Anna and James around 1921.

Steve and Josie Walko stayed in Zeigler to run the ever-profitable business there. Their daughter Dorothy was born there in 1924.

James continued to excel as a model student in ESL, with at least two more years of perfect attendance. This child of saloon keepers would remain enamored with education and learning, especially history, for years. At some point, he decided to make a career of teaching it.

In 1922, his father Louis Kalish paid $52,000—more than $900,000 in today’s money—for the Savoy Hotel at 201 Missouri Avenue in East St. Louis. Located at the intersection with 2nd Street, it sat just two blocks from the Relay Depot, the city’s primary passenger train terminal at the time. Given the nature of the family business, the Savoy Hotel was in precisely the right part of town.

In the 1880s, East St. Louis began raising its streets to keep homes and businesses dry when the Mississippi flooded. The massive project wasn’t quite finished in 1903, when the city found itself under 39 feet of water during one of the worst floods ever recorded. The area around 2nd and 3rd Streets, between Missouri and St. Louis Avenue, had not yet been raised, so floodwater collected there like in a valley. The metaphor stuck.

Property owners in “the Valley,” as the area was known for decades thereafter, grew tired of waiting for improvements. Many simply walked away from their ruined houses on muddy streets. Tavern owners and prostitutes were only too happy to take over the abandoned properties—and they preferred the streets that way. Whenever the city filled a pothole, bleary-eyed working girls would dig it out the next morning, forcing cars to slow down and making it easier for them to hop on running boards and offer their services.

City officials might have shut down this corridor of unseemly trades, but doing so would have cut off their most reliable source of municipal revenue. Many major East St. Louis employers—stockyards, meatpacking operations, and factories of all sorts—had shrewdly located just outside city limits to avoid paying local taxes. Monsanto Chemical and the National City stockyards went so far as to incorporate their properties as bogus municipalities inside city limits to make the evasion permanent.

Owners of Valley taverns with backroom gambling and prostitution—known euphemistically as “resorts”—had no such options. The wads of cash they handed over for licenses, fees, and bribes kept the struggling city afloat.

Back in East St. Louis with his Zeigler earnings, the once penniless immigrant Louis Kalish was doing extremely well, running the Savoy Hotel and living there with Anna and James.

The Savoy was perfectly positioned to meet the ongoing demand for drink—Prohibition or not—and women. The ground-floor tavern became a speakeasy, and there were plenty of rooms upstairs for both family and prostitutes.

At some point, the Savoy became the favored hangout of the Shelton gang, archenemies of Charlie Birger’s crew in the bloody rivalry for control of the illegal liquor trade. The Birgers met at a place across the street.

Louis had a reputation for generosity toward his patrons, including railroad workers—nearly as numerous in ESL as packinghouse laborers. Maybe he sympathized with financial struggle. Or, as a heavy drinker himself, perhaps he simply grew sentimental and generous when in his cups.

“Men would come in with hard luck stories and he’d lend them money, and never get paid back,” recalled his granddaughter Lorraine. One debtor, to settle his tab with Louis, signed over the deed to an undeveloped lot at 5607 Lake Drive.

Around the time Louis Kalish moved back to East St. Louis from Zeigler, his sister—and presumed war widow—Mary Kavalir and her son Frank were making ends meet in what was then Yugoslavia. One day there was a knock on the door. Standing outside was Franz Kavalir, very much alive. He had not died after all. Mary opened the door, saw her husband, and promptly fainted.

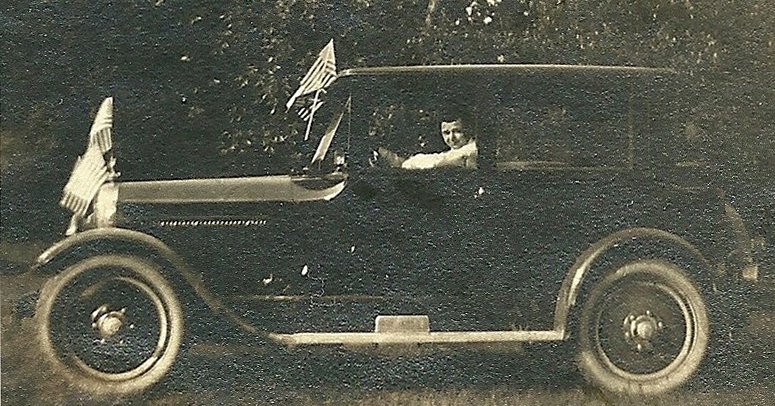

In 1924, Franz and Mary, along with 11-year-old Frank and 4-year-old daughter Emica, left Europe and arrived at Ellis Island before continuing to East St. Louis. There, the newly prosperous Louis picked up his sister and her family in a Model T Ford.

Sadly, young Emica died shortly after arriving in East St. Louis.

Franz, Mary, and Frank lived for a time at the Savoy, helping to run the place in exchange for lodging. Frank had a paper route, one that included the Savoy speakeasy, where he would lay copies of the East St. Louis Journal on tables. Each paper cost him two cents. Louis would pay him a dime per copy—and sometimes a quarter. “I made more money putting papers on those tables than I did from all my customers the rest of the day!” Frank recalled years later.

Louis did not handle his rise from packinghouse laborer to Valley hotelier well. This Louis was no saint. As an alcoholic with unlimited access to liquor, the drink did not always soften him as it did when listening to a despondent patron. At home, he would routinely force Anna and James to hide beneath the stairs while he trashed the house with a gun in his hand, vowing to kill them both.

The terror ended when Louis died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1926. His brother Joe then managed the Savoy, with brother Mike apparently involved as well. Within months, Louis’s widow Anna became seriously ill—of what is unknown—and traveled to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for treatment. It didn’t help. She came home with an infection that hastened her death in 1927. Fifteen-year-old James was now an orphan.

Louis and Anna didn’t leave their only child much money, but he did inherit the Savoy Hotel and the plot on Lake Drive. He would later appreciate the Lake Drive property but forever despised the hotel and left its operation to Uncle Joe.

He soon learned that Joe—an alcoholic as bad or worse than his father—was drinking away any profits. James remained stoic, and even thanked God for what he saw as a silver lining to this dark cloud.

After Louis and Anna’s deaths, Steve and Josie Walko left Zeigler and returned to East St. Louis for good. They, along with others in the family, took over the Savoy. With their Zeigler profits, the Walkos built a brick home at 1324 North Park Drive, across from Jones Park.

They took in their nephew James as if he were their own child, giving him a home across the street from a park with a natural swimming pool so large that lifeguards patrolled in rowboats, plus a quarter-mile track and baseball fields.

James and his cousins—Steve Jr. and Ed Walko—took full advantage of the park. Soon, in addition to his academic gifts, James was known for athleticism and dedication to physical fitness. But his interest in teaching never wavered. His cousin Frank Kavalir, at age 84, recalled how James would tutor him and offer a dime for every high mark (“S”) on a report card. “He was a wonderful help in my schooling,” Frank said.

We don’t know exactly what Leonard Krokvica did in Zeigler, but we do know he drank. He later bragged about consuming an entire bottle of wood alcohol there and living to tell the tale. Following the Walkos, Leonard and Marie also returned to East St. Louis. Leonard got a job as a railroad switchman but was often too drunk to show up, so Marie would perform the dangerous work herself in the dark of night, hoping no one would notice and cost Leonard the job.

Eventually, Marie told her husband to live elsewhere. By 1930, Leonard was living alone at the Savoy Hotel. Marie lived a couple of miles away at 1311 Exchange Avenue with their 21-year-old daughter Mary.

Leonard struggled with English all his life, never mastering it. His grandchildren, who called him “Daddo,” didn’t converse with him much. Family recalled that he often seemed to be “just taking up space.” Marie, known as “Bobby,” was the opposite—she didn’t drink, loved kids, learned English well, and was exceptionally resourceful and hardworking.

“To me, she was a superwoman,” recalled her granddaughter, Lorraine Durbin. “There’s just nothing she could not do.”

After losing both parents, teenage James was living as well as one could in East St. Louis—nice neighborhood, park across the street, surrounded by family. But luck would turn again in 1929—and not for the reason most Americans remember that year.

Like Louis before him, Steve Walko had made good money in Zeigler. From their comfortable home across from Jones Park, he, Josie, their children Steve, Ed, and Dorothy, and effectively James enjoyed the best that East St. Louis offered. Then came 1929.

Most people who lost everything that year blamed the stock market crash. Steve had only gambling to blame. He lost every penny—and the house—betting on a pack of ponies at an East St. Louis track. He also lost his job.

With no house and no money, the six-member household—Steve and Josie, their three kids, and 17-year-old James—moved into the Savoy. It still belonged to James and continued to prosper as a brothel, speakeasy, and Shelton Gang hangout. Steve managed it; Josie cleaned rooms and kept house.

The three-story hotel had 33 rooms, and Josie cleaned all of them. With paying customers in every room, the family lived in a two-room space on the first floor with no kitchen. How they prepared meals is anyone’s guess.

James hated living at the Savoy. But he stayed stoic and doubled down on his studies, convinced that education would carry him out of both the literal and figurative place he didn’t want to be. He excelled at East Side High School and continued his fitness regimen, soon able to do 100 push-ups without breaking a sweat. (He maintained that nightly ritual into his 80s, until his doctor finally told him to stop.)

He surprised no one by applying to and being accepted at Northeast Missouri State Teachers College in Kirksville—now Truman State University. He had money for tuition, but not transportation. Being from East St. Louis, he knew his way around railroads, and there were plenty of freight trains to ride home for visits.

On one of those visits in 1933, James Kalish met and married Bernice Malec. Theirs would prove a model marriage with many happy consequences.

Next: 15. The Kalish and Krokvica Families 1934-2011

Previous: 13. The Zeigler Era 1912-1922