After they married in 1928, the first home of William and Ann Durbin (at some point she trimmed her name from Anna to Ann) was an apartment on 30th Street in East St. Louis above the home of a Mrs. Lyons, who took an immediate liking to the young couple and made every effort to look after them.

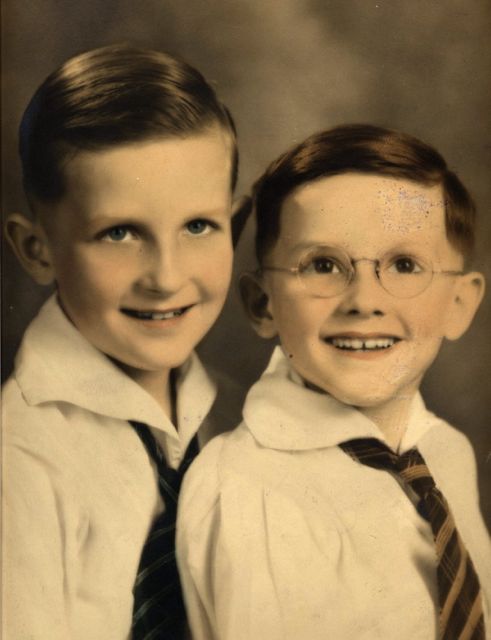

Their first child, William Pius Durbin Jr. (hereafter Bill Durbin), was born in 1929—just in time for the stock market crash and the Great Depression that followed. His first bed was a dresser drawer. Mrs. Lyons gave William and Ann a sterling silver cup—no trivial gift in those days—engraved with their son’s name.

Bill’s first brother, Robert Emmet Durbin (hereafter Bob Durbin), was born in 1931. He was named for the Irish nationalist leader Robert Emmet, whose 1803 “Speech from the Dock,” delivered just before his hanging for treason, stirred the people of Ireland the way Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail would stir Americans six decades later. Irish schoolchildren were made to memorize it. As an adult, Bob once watched a London bartender, one of those former schoolchildren, stand atop a beer box and recite it from memory.

Around the time Bob was born, the family moved to the 500 block on the east side of 33rd Street, where they lived for about a year, and then to Belleview Avenue, two doors from 29th Street. Bill entered first grade at the parochial school at St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church while they lived there.

Money was always tight. Fortunately, Bill and his brother were lucky to have a father with a good job on the railroad and a mother who was as strong, smart, and determined as any woman who ever stepped foot in East St. Louis. No economic downturn, no matter how great, was going to defeat Ann Durbin.

One thing the family never ran out of was eggs. William ran the feed house at the New York Central Railroad and came home with an armful every day. Bill and Bob got hooked on fried egg sandwiches, and their mother sold extras to neighbors.

In 1935, Ann Durbin was naturalized as a U.S. citizen. She missed one question on her exam, saying that presidents were elected by popular vote rather than the electoral college. The examiner agreed the question was unnecessarily tricky and let it slide.

In 1936, the family moved to 484 29th Street—next door to Ma and Pa (Margaret and Oscar) at 486. Unfortunately, Ann did not like living beside her in-laws. Tensions between her and Ma, and with her sister-in-law Mary, grew quickly. After less than a year at 484 they moved to 1531 North 41st Street.

There, in 1937, William brought home for eight-year-old Bill a library card and a book on Roman mythology. The surprise gift turned Bill into a voracious reader and lifelong lover of books. That same year a traveling salesman convinced his parents to buy an accordion for next to nothing, in exchange for a commitment to pay for lessons.

Knowing the sacrifice his parents were making, Bill took the lessons seriously. He mastered the complicated instrument and for decades thereafter could play any number of tunes by heart. It made his mother happy to hear him play, so he performed whenever asked. And when he went into the Navy years later, the accordion went with him.

In mid-1939, the family moved a few blocks to North 40th Street—the house number might have been 1341, but we’re not sure. Bill would recall it as the nicest house they ever lived in. Apparently it was too nice, because within months they could no longer afford the rent.

When William’s father, Oscar, found out, he bought them an affordable house at 441 North 33rd Street. It was a shotgun house, so-called because one could supposedly fire a shotgun from the front door and have the buckshot exit the back door without hitting anything. They moved there in January 1940.

The house sat across the street from the so-called Acid Hills, where ALCOA, the aluminum producer, was said to have dumped its industrial waste into piles, which became favorite terrain for neighborhood boys on their bikes. Bill and Bob were among them, instructed to keep an eye out for huge clouds of chemical dust that would occasionally roll across the street. When they saw one, they were instructed to run home and shut the windows.

These were war years. Indeed, World War II was the defining event of Bill’s childhood. He had a paper route and would read the East St. Louis Journal before delivering it. One afternoon he read that sugar was about to be rationed. On his way home he stopped at several stores and bought up as much as he could carry on his bike—nearly thirty pounds of it.

His mother gave him the 1940s equivalent of a high five. His father did not, pointing out that hoarding in wartime could land you in serious trouble with the law. Bill never did that again.

In 1944, Oscar brokered a truce between his wife and daughter-in-law. Later that year, William and Ann moved their family back to 484 29th Street, next door to Ma and Pa. That was also the year Bill and Bob got a little brother: Richard Joseph Durbin. He would go by Joe for much of his youth, and later by Dick Durbin.

For the three sons of William and Ann Durbin, one of the defining features of their ESL youth was the sheer number of extended family members nearby—eight aunts and uncles, and more than a dozen great aunts and uncles. Adding in all the cousins, there were more relatives than they could possibly keep track of. But some of those relatives left lasting memories.

Ma’s sister Mary—Aunt Mame to the kids—had the most wealth of anyone in the family, chiefly from a settlement after her husband was killed working on the railroad. But you would never know of her ample money from her modest home and miserly lifestyle. When needing to cross the Eads Bridge to St. Louis, she paid the five cents to walk—the bus cost fifteen cents. She had her nephews save up old newspapers, then wind them into tight roles and bind them with wire, which she burned in the furnace to stretch her coal supply. Only after she died, when survivors found bank accounts she had forgotten about and enough assets to give even distant nephews hundreds of dollars each, was her hidden wealth revealed.

Ma’s brother Lawrence was at the other end of the financial spectrum, hitting up even the littlest kids in the family for pocket change. Lawrence came and went, working menial jobs at railroad restaurants, then disappearing and reappearing, living with Ma when he was in ESL.

Ma’s brother Pete was also known for being forever low on funds, and what little funds he did come across were likely to be spent drinking. When Pete developed severe cataracts, he decided he’d rather be blind than spend money on their removal. He moved in with Ma, and liked to sit on her front porch during electrical storms because he could tell when lightning bolts went off.

John was another of the Gaul siblings to lose his eyesight. Athletic as a youth, winning one county running race after another, he went off to join an artillery unit of the U.S. Army. Something went wrong and he came home blind. Ma took him in.

Ma’s sister Kathryn, Aunt Kate, married Ira McPherson, and by 1948 would have three grandchildren in the pool of ESL cousins, all related in one way or another. John McPherson was eight, his brother Gerald was six, and their cousin Thomas Schmitt was seven.

On September 11, 1948, those three boys learned the carnival was in town. As the elated trio bolted across State Street, a car struck all three kids at once. None survived. It was the kind of tragedy—all but forgotten now, as relatively few people alive in 1948 ESL are still with us—that sent a wave of unbelievable shock through countless relatives, no matter how distant.

The three sons of William and Ann Durbin, growing up in the 1940s in their modest home on 29th Street in East St. Louis, would be excused for taking for granted the bounty of nearby family and the range of experiences that came with it. They also had front-row seats to three of the nation’s great domestic battles of the twentieth century—for women’s rights, civil rights, and union rights.

Ann Durbin was a feminist before anyone used the word, demonstrating at any opportunity she could do both a woman’s work and a man’s. She would not hesitate to paint a room or repair a lamp, and took business school classes so she could work in an office. She eventually got a job as a clerk at the New York Central Railroad, where her husband William was Chief Clerk. Typical for the day, his desk was on a raised platform facing out on a large room of symmetrically arranged desks facing his. Ann worked at one of those desks.

William Durbin was a union man to the core. He took a stand for the rights of workers—of any skin color—as he rose through the ranks on the railroad, even after his promotion into management, when passions for worker rights are often put to test. He navigated well the fine line between the interests of management and worker and decided at the age of thirty-eight to apply his skills in the political arena. He was elected to the County Board of Supervisors in 1944 and within three years found himself chairman of the Finance Committee. He also found himself in a battle between personal ethics and government corruption.

William Durbin was offered bribes more than once, from people hoping to curry favor with this public official, one time accepting a cigarette and noticing just before lighting it the tobacco had been replaced with a $50 bill—about a week’s pay. Struggling with whether he should accept it, he went to a priest for advice.

We don’t know what the priest advised, but we do know William took an all-or-nothing stand in the 1949 election for Chairman of the County Board, when he refused to back a long-time family friend who apparently had no problem at all with the rampant corruption.

Another bribe, for nearly a half a year’s pay, which he turned down, wouldn’t sway William Durbin. It appears bribery did sway others. His candidate lost, narrowly, and the very day after the election his former friend stripped William Durbin of his committee chairmanship. The foray into politics, for this Durbin family, was over. Or so it seemed in 1949.

Bill Durbin attended eight years of elementary school at St. Elizabeth’s. He struggled academically, earning generally poor grades, but he excelled in composition, penmanship, and oratory. Those strengths may have helped him earn a scholarship to St. Henry’s Preparatory Seminary in Belleville. The so-called minor seminary provided young men with a high school education while preparing them for major seminary and, ultimately, the Roman Catholic priesthood.

For his mother—who had long prayed that one of her sons would become a priest—his enrollment at St. Henry’s was the fulfillment of a dream. For Bill, it was a mistake. He went through the motions for the first two years, but by the third, the strain of trying to please a mother who expected him to become a priest while knowing he did not want that life made him ill. He spent weeks in the infirmary before finally gathering the courage in 1945 to tell his parents he was leaving seminary.

He finished the remainder of high school—about a year and a half—at Central Catholic, which later became Assumption High School. To earn money, he worked nights and weekends at the New York Central Railroad, where his father William was by then Chief Clerk. His dad assigned a Black stevedore named Jesse to train him. Jesse knew everything there was to know about the job and made clear to Bill the absurdity of judging someone by their skin color.

After graduating in 1947, Bill stayed on at the railroad while enrolling at Belleville Junior College, just outside East St. Louis. Working nights and attending classes after his shift left him sleep-deprived, and his mind foggy during lectures. His parents struggled to understand why he bothered with school. He was the first Durbin in this line to attend college, and his father was eager to groom him for a lifelong career at the New York Central.

But Bill Durbin wanted something different. Tensions with his mother helped him decide what that might be. Ann Durbin never got over her disappointment at his decision to leave the seminary. She refused to speak to him for months. Bill remained devoted to both parents, but for reasons no one could explain, nothing he did could ever seem to please his mother. One evening in 1948, some friends arrived to pick him up for a night out. As he reached the door, his mother stopped him and ordered him to stay and wash the dishes.

The humiliation helped him decide it was time to put distance between them. The country was still basking in the postwar euphoria of victory in World War II. Bill had long regretted being too young to serve in what people called the “Good War,” and he had already considered a military career. With no wars underway in 1948, the United States had dramatically reduced military spending but still maintained a standing Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. So one day he went to the Navy enlistment office.

The recruiting officer welcomed him with a smile, a handshake, and a cup of coffee. As he passed it over, he noticed Bill’s fingernails, chewed down to the quick.

“Son, you can’t join the Navy with fingers like that,” the officer said. “It’s a bad sign.”

Bill was momentarily crushed—until he realized it was a solvable problem. He let his nails grow back, trimmed and polished them until his hands looked like those of a movie star, and within a few weeks used them to sign his enlistment papers. At eighteen, Bill Durbin committed to serve three years in the United States Navy. It would prove to be a turning point in his life.

Although he knew it was possible, he did not expect to see combat; the nation was at peace when he enlisted in 1948. But in June 1950, North Korea—with support from China and Russia—invaded South Korea, igniting the Korean War. Bill Durbin found himself aboard a destroyer, firing guns in shore bombardments, clearing naval mines in the Yellow Sea, and wondering if he would make it home alive.

While home on leave in 1949, he met Lorraine Kalish. They married in 1952, eight weeks after his discharge, and eventually had ten children—nine boys and one girl. The family relocated briefly to Columbus, Ohio, in 1958 so Bill could pursue a graduate degree at Ohio University. In 1962 they moved from East St. Louis to nearby Fairview Heights, Illinois, and in 1973 to the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., where they would spend the rest of their lives.

Bill’s brother Bob also enlisted in the Navy, and for nearly a year the brothers served on the same ship. After his discharge, Bob took a job at McDonnell Aircraft (later McDonnell Douglas) in St. Louis. In 1953, the company offered to relocate him to California. He accepted and moved to the state that would be his home for the rest of his life. In 1956, he married Nancy Bennett. They had two children.

Like nearly everyone in the 1940s, most members of William and Ann’s family smoked cigarettes. Reaching for a smoke then was as habitual as reaching for a water bottle or coffee today. William Durbin smoked two and a half packs a day. The habit soothed his nerves, but it also killed him. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in early 1959, while Bill and his family were still living in Ohio. By the time they had returned to East St. Louis, William was bedridden at St. Mary’s Hospital. Exploratory surgery confirmed the worst: at fifty-three, he had no chance of survival.

Bill visited his father every day, shaving him, reading him the newspaper, and doing anything he could to provide comfort. His brother Bob came too, slipping their father sips of gin when the nurses weren’t looking.

William Durbin spent eighty days in the hospital before dying on Friday, November 13, 1959, with his family at his bedside. He took his last breath at 12 p.m., just as the Angelus bells rang from nearby St. Henry’s Church.

Over five hundred mourners attended his wake. Among them was Maurice Tolden, a Black coworker, who stood outside on the sidewalk in deference to strict racial customs. When Bill noticed him, he immediately escorted him inside—a small act of defiance his father would have appreciated.

In 1962, William and Ann’s youngest son, Joe, graduated from Assumption High School and left for Washington, D.C., to attend Georgetown University. During his senior year he worked as an intern for Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, who mistakenly called him “Dick.” The name stuck.

Dick stayed at Georgetown for law school, then returned to Illinois and settled in Springfield. He married Loretta Schaefer in 1967, and together they had three children.

He opened a law practice and served as legal counsel to Lieutenant Governor Paul Simon, who helped inspire Dick’s entry into politics. After losing races for the Illinois Senate in 1976 and for Lieutenant Governor in 1978, Dick narrowly won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing the same district once represented by Abraham Lincoln.

In 1996, he moved across the Capitol to the U.S. Senate, eventually becoming Assistant Majority Leader. From that position, he encouraged a first-term senator from Illinois—his friend and protégé—to run for president. His name was Barack Obama.

William Durbin never lived to see his youngest son become one of the most prominent Democratic politicians in the country. One can only imagine his pride. Among Dick Durbin’s early accomplishments in Congress was writing the law that banned smoking on airline flights under two hours, a change that helped set off a wave of anti-smoking legislation—too late for his own father, but life-saving for millions of others.

In 1964, Ann Durbin followed her son Bill to Fairview Heights, building a house for herself at 112 Primrose Lane—right next door to Bill and Lorraine at 114. She told no one of her plans beforehand.

For the Durbin kids, having Grandma next door was a delight. Her modest house was filled with treasures she was always eager to share: a coin collection, a stereo, a color TV, encyclopedias, and endless games. She was a master of crossword puzzles, completing one every day—not in pencil like most people, but in ink. She had no need for erasers.

As little Ona Kutkaite, she had arrived in America from Lithuania in 1911, disembarking in Baltimore. Maryland was the first place she ever set foot in the United States. It would also be the last. In 1986, she moved there once more—her grandson Ken drove the U-Haul, and Congressman Dick Durbin drove her car. She rented for a while, then bought a condominium in downtown Bethesda, near Bill in Kensington and just a few miles from the shared Capitol Hill rowhouse where Dick lived with three other members of Congress. That spartan residence later became known as the Animal House, immortalized in the 2013 TV series Alpha House, starring John Goodman.

Living in Maryland, surrounded by two of her three sons, Ann remained a radiant presence. She spent holidays at Bill and Lorraine’s house on Thornwood, arriving from her sunlit apartment several floors above the street, where she lived with her cat, Sammy.

During the Clinton administration, members of Congress were invited to bring their mothers to the White House for Mother’s Day. Bill and Lorraine helped Dick wheel Ann forward to meet the president and first lady. She took their hands and held them, stunned by the distance she had traveled—from a corner of a warehouse floor in East St. Louis to the carpeted corridors of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

As a young mother, Ann had longed desperately for a priest among her sons. Fate, and her sons, had other ideas. We can only presume she ultimately felt extraordinary pride in how things turned out for her three sons, fifteen grandchildren, and dozens of great-grandchildren.

In 1997, Ann Durbin died at eighty-seven at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda. She had defied death many times before, surviving illness after illness, but at last her heart gave out. When nurses found her, she was slumped in bed, a crossword puzzle in one hand and a pen—of course—in the other.

Not long after her passing, Bill did something he could never bring himself to do while she was alive. The accordion she had sacrificed to buy him in childhood still sat in his closet. It had long since dried out and become unplayable. He took it to the county dump with his son Ken’s help. After setting down the case for the final time, he headed back to the car, then stopped. He turned around and went back. Crouching over the instrument that had meant so much to him and his parents, he pried off the name tag—“BILL”—and slipped it into his pocket. And then he went home.

Next: 10. Austria-Hungary

Previous: 8. Robert & Marcella Kutkin 1873-1960