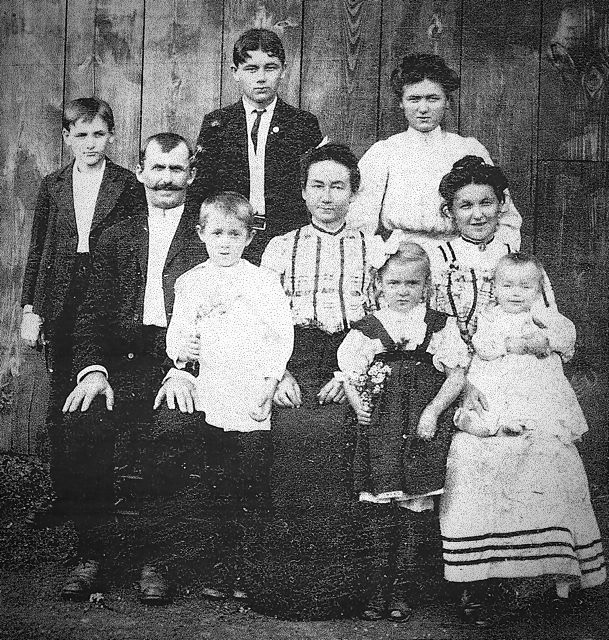

I am one of ten kids of Bill and Lorraine Durbin. My dad’s father died before I was born, but my mom’s dad, James Kalish, was a regular presence in my life as a kid.

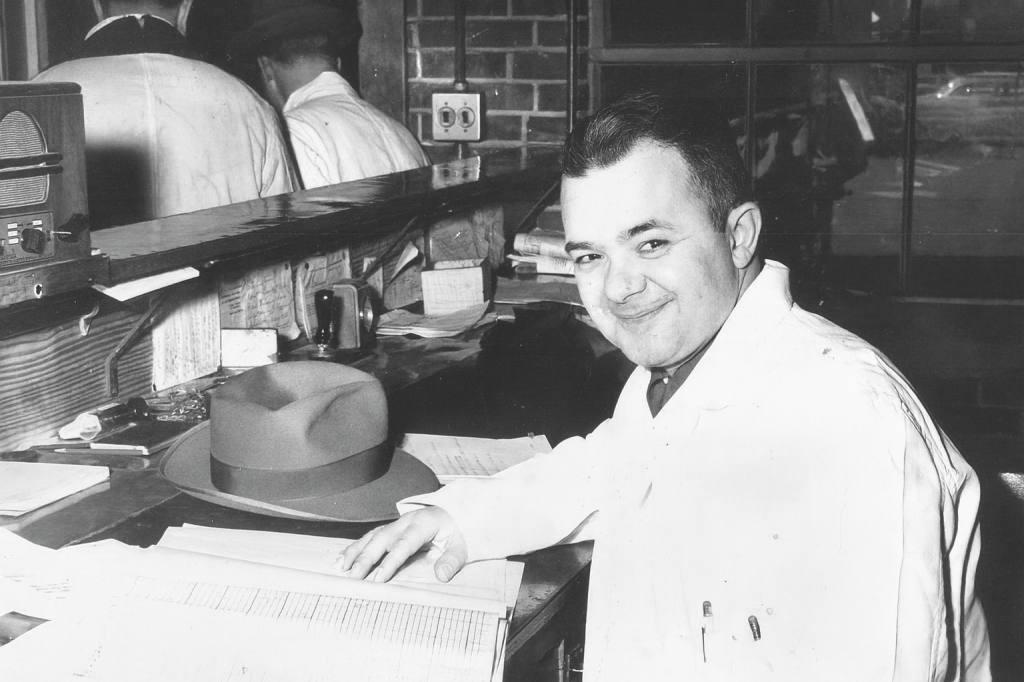

In the 1960s, he and his wife Bernice lived in East St. Louis, Illinois, and we lived in nearby Fairview Heights. They came to our house all the time, or we went to theirs, and there is one thing that struck me about Grandpa Kalish more than anything else: He was always happy, always impressed with whatever his grandkids were up to, and always so positive—about everything.

As a child, I knew nothing about the childhood of our Grandpa Kalish, nor his family history, nor what his life had been like before I met him. Only now, decades later, do I know enough about his early years to realize how incredible it is that he was so happy in his later years.

James Louis Kalish was born in 1912 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. For much of his youth he went by Jimmy. His parents were Louis and Anna Kalish—her maiden name was Krokvica. Both were born in the late 1800s in what is now the European nation of Slovakia. At the time, Slovakia was part of the massive Austro-Hungarian Empire, which ruled over much of eastern Europe for centuries before its collapse in 1918. Jimmy’s parents hadn’t known each other back in Europe. They met only after immigrating.

Jimmy’s father, Louis Kalish, was the second of six children of Stefan and Katarina Kalish—she went by Kata. After starting their family in present-day Slovakia in the 1880s, they moved to what is now Croatia in search of better job opportunities. There, Stefan became a notary in the town of Banova Jaruga.

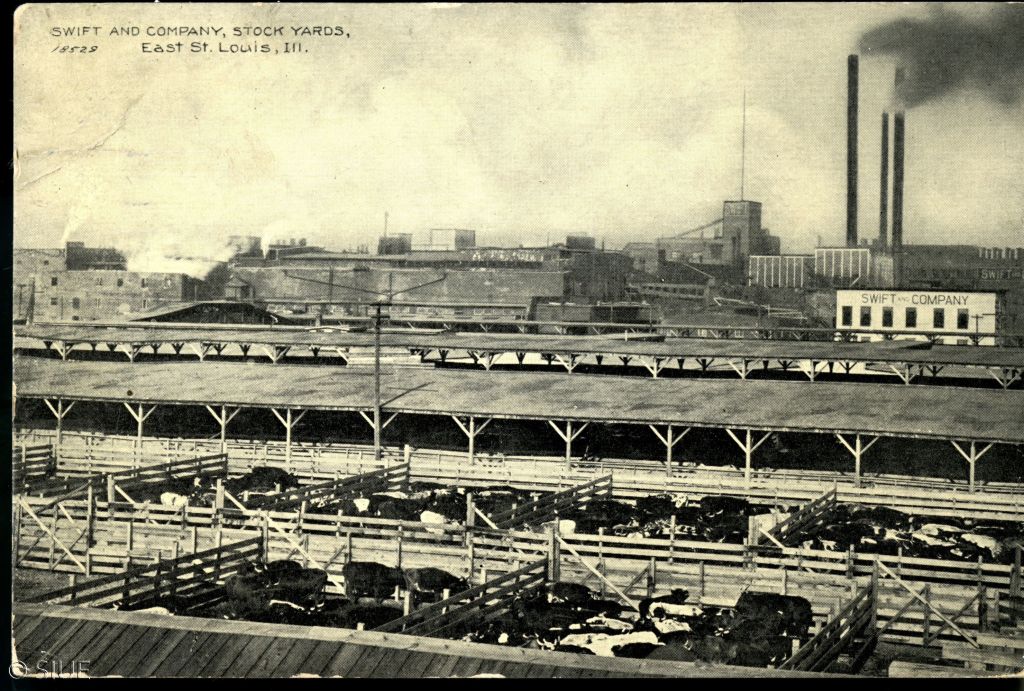

In 1903, 17-year-old Annie Kalish, the eldest of Stefan and Kata’s children, fled the family—some say to escape an abusive father. She emigrated to America and soon found work at the Swift and Company meatpacking operation in East St. Louis. The next year, Annie’s brother Louis followed his sister, at age 15, and soon the Kalish teenagers were both working at Swift.

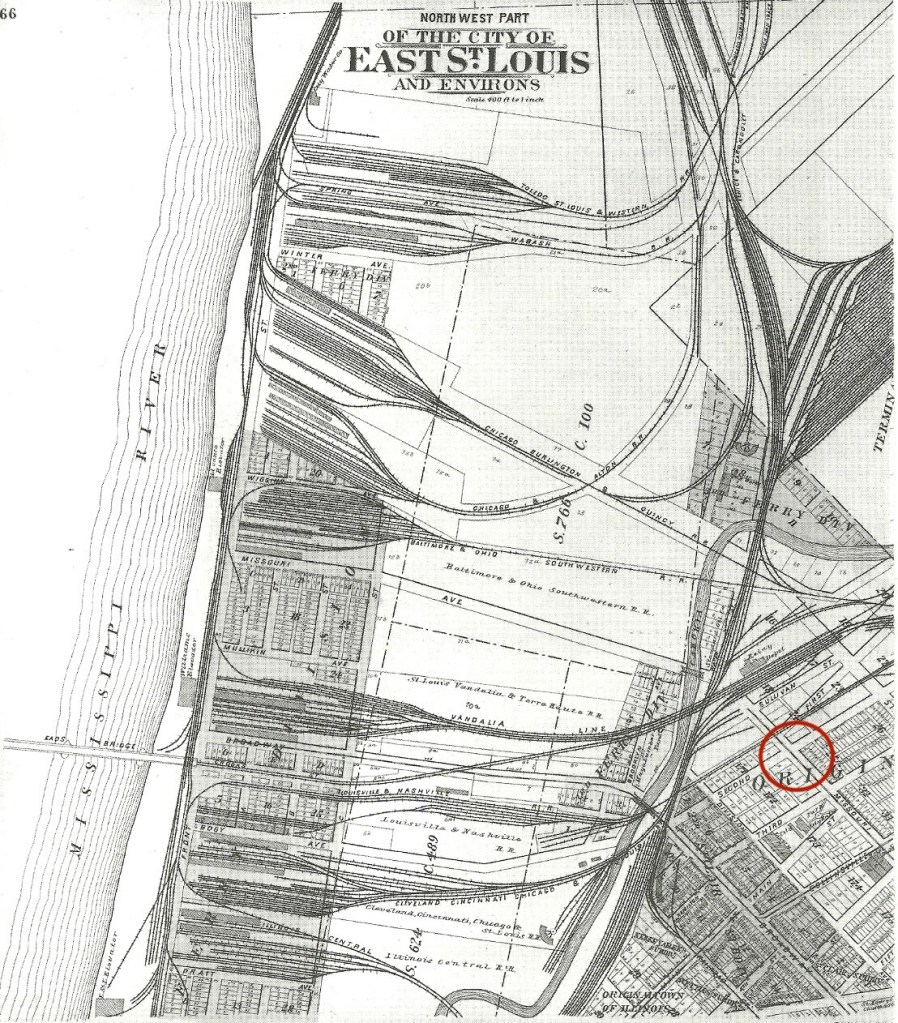

East St. Louis in those days was a magnet for penniless immigrants looking for work. After the Eads Bridge opened in 1874—it was the first to ever cross that part of the Mississippi River—the nation’s railroads all put terminals there. After Gustavus Swift pioneered the use of refrigerated railroad cars to ship packaged meat, East St. Louis became a natural location for a centralized slaughtering and meatpacking operation. By the dawn of the 1900s, several meatpacking giants had jobs in East St. Louis for anyone willing to work long hours doing dangerous work for little pay.

Back in Europe, Stefan and Kata did not like how their two eldest children had fractured the family. In 1906, they and the remaining four kids packed up and emigrated to America. But there was a problem at Ellis Island.

Five-year-old Joe Kalish had contracted polio when he was very young, leaving him with weak legs. After his family’s two-week journey across the Atlantic, immigration officials decided he was not healthy enough to be allowed into the United States. They refused entry. His mother Kata, distraught, pitched a fit until the official changed his mind. Relieved, the family continued on to East St. Louis, where they reunited with Annie and Louis.

Stefan had no trouble finding work in East St. Louis, joining his kids at the meatpacking houses. But the manual labor was a step down from his position of respect as a notary public back in Europe. He swallowed his pride and did his work.

Jimmy’s maternal grandparents were Leonard and Marie Krokvica. They married somewhere in present-day Slovakia in 1892 and had two daughters: Anna and Josephine—she went by Josie.

We don’t know what kind of work Leonard Krokvica did back in Europe, but around 1903, shortly after Josie was born, he was drafted into the army. Leonard did not like that idea, so to get out of serving he fled to America, taking all the family money with him, promising to send for his wife and daughters as soon as possible. A year went by with no word from Leonard. Then two. Marie gave him up for dead.

Then Marie got word from a relative that her husband was very much alive, living in East St. Louis. Marie sold every family possession they had to raise money to get her and her daughters over there. Eventually, in 1908, Marie caught up with Leonard—probably intoxicated. He was living in a flophouse, drinking a lot and not much else. And the family money was gone. He had drunk it all.

Marie Krokvica had no choice but to find jobs for her and her teenage daughters—school was out of the question. So all three went to work in the packinghouses for five or ten cents an hour, ten hours a day, six days a week.

We don’t know if Leonard worked or not. We do know they all lived together for at least a short while, because later in 1908 their daughter Mary Krokvica was born in East St. Louis.

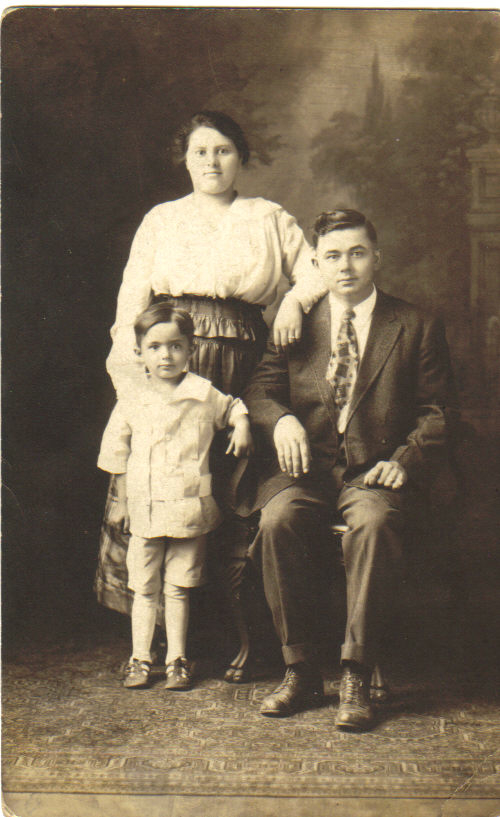

We presume Louis Kalish met Anna Krokvica working at a packinghouse. The fact they both spoke Slovak, as they struggled to learn English, was no doubt a factor.

Their marriage on the third of September 1910 was officiated by a justice of the peace, in part because they were in a hurry. A few weeks later, on September 29, Anna Kalish gave birth to a baby girl. They named her Meri. Sadly, she lived only a short time. We don’t know how long exactly.

By 1912, 24-year-old Louis had been at Swift for eight years, working for ten cents an hour, doing who-knows-what turning cows and pigs into packages of meat. Then he was offered a 50 percent raise, to fifteen cents an hour, if he would relocate to a meatpacking operation in Oklahoma City, 500 miles to the west. He and Anna, who was expecting another child at the time, jumped at the opportunity and took a train to Oklahoma. Their son James was born there in August.

Shortly after Jimmy’s birth, however, his parents learned something they hadn’t been told before leaving East St. Louis: The man who held Louis’s job before him had been fired—and he promised to kill anyone who tried to take his place.

The death threat was enough to convince Louis and Anna to get back on a train with baby Jimmy. Dejected, Louis went back to his old job at Swift for ten cents an hour.

Not every Kalish immigration story would work out. Just like Latino immigrants in the United States today, our Slovak ancestors in the early 1900s were looked down upon all the time. After six years in East St. Louis, Stefan Kalish decided he couldn’t take it anymore. He especially disliked what co-workers called him.

“I’m no hunkee SOB!” he complained. The hunkee part of the ethnic slur apparently came from the earlier bohunk, which referred to a Bohemian from Hungary. The term hunkee would later evolve into honky, a slang American term used in the 1960s for a white person.

In 1912, as Louis and Anna returned from Oklahoma City with baby Jimmy, Stefan and Kata Kalish returned to Austria-Hungary with 10-year-old daughter Mildred, leaving their other children in East St. Louis.

Leaving 11-year-old Joe behind was an agonizing decision. But having been nearly turned back at Ellis Island six years before, Kata did not want to risk taking him out of the country for fear he would never be let back in. So Joe said goodbye to his mom, dad, and sister Mildred.

Back in Banova Jaruga, Stefan and Kata grew plum trees and made brandy, called slivovitz, along with other goods. Unfortunately, World War I erupted soon after the Kalish family’s return to Europe, following the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Stefan, Kata, and little Mildred Kalish were in Austria-Hungary as it collapsed in 1918, finding themselves struggling in a country renamed Yugoslavia, which would later be subdivided into the countries in that region of Europe today.

After losing his mother at age 11, Joe Kalish had a rough time transitioning into adulthood. The physical disability in his legs certainly did not help. It’s doubtful he could have worked in the meatpacking plants without healthy legs. His inability to work in meatpacking would influence the course of this family history.

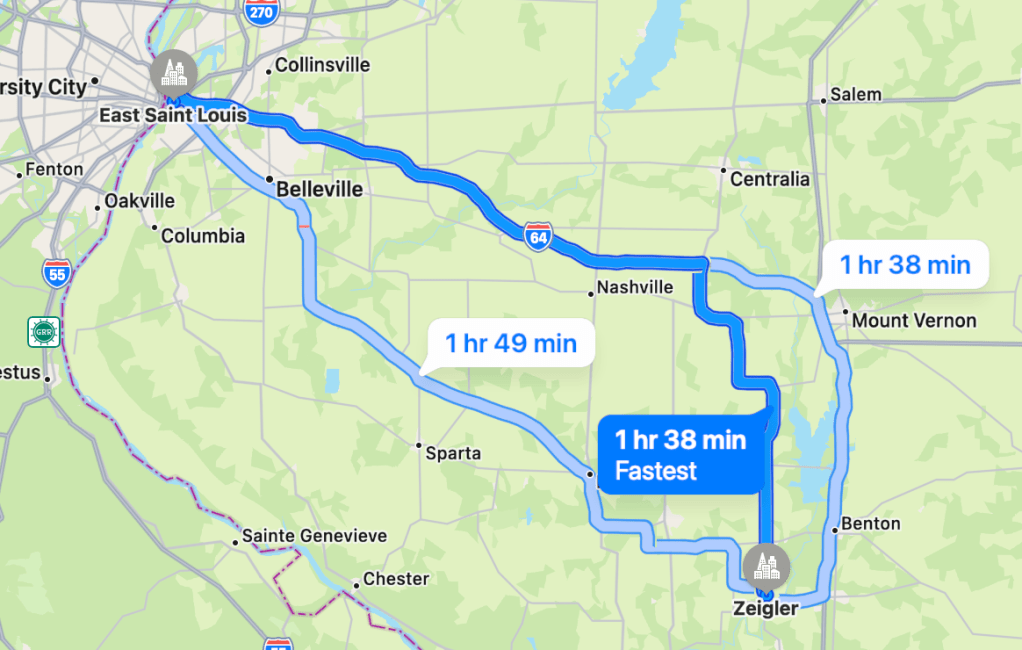

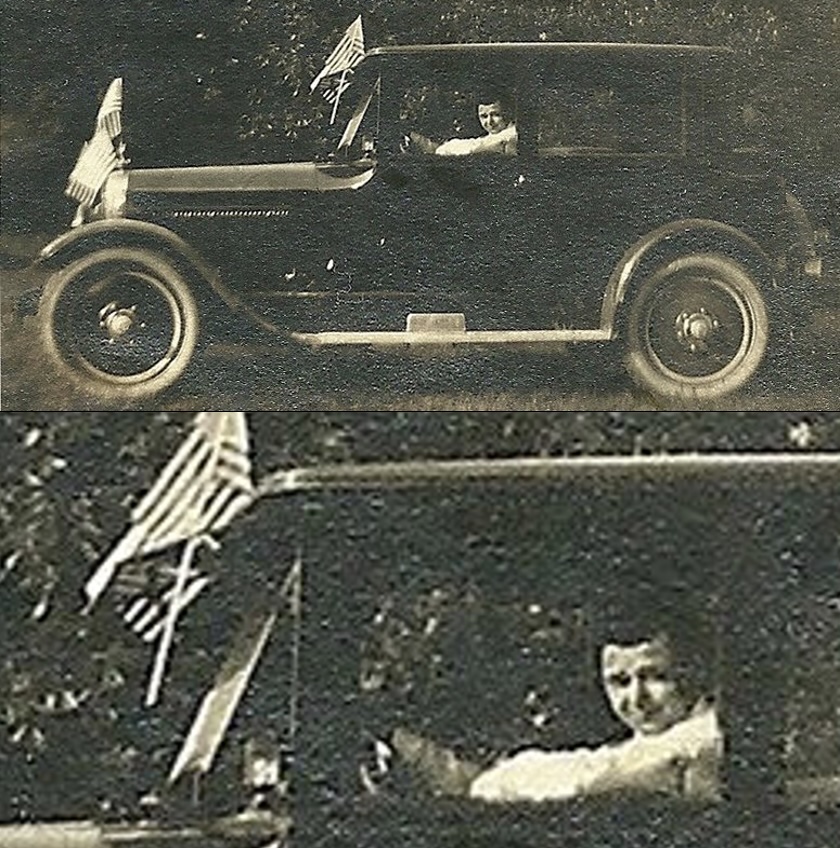

As a teenager, Joe was known as a lively and resourceful guy who played the accordion and piano, rode a motorcycle, ran a filling station, liked to play checkers, and liked to drink. At some point, Joe bought a Model T Ford and began a taxi service—for prostitutes, shuttling them between East St. Louis and the Illinois town of Zeigler. He charged $5 each way, or more than $150 in today’s dollars.

Located about 100 miles southeast of East St. Louis—a round trip in a Model T could take five hours—huge coal deposits had been discovered in Zeigler in the early 1900s. This led to the opening of mining operations.

Mines require miners, and miners enjoy liquor and the company of women. Some miners are willing to pay for both. We have no idea how Joe learned about the little town of Zeigler and its need for services, but East St. Louis had plenty of liquor and plenty of prostitutes, ready for loading into his car for the long and bumpy ride to Zeigler.

After retreating from Oklahoma City, it didn’t take long for Joe’s brother Louis to grow unhappy about his 70-hour workweek at ten cents an hour. But then, after learning about Zeigler from his brother Joe, he got an idea.

The miners down in Zeigler needed not just liquor and the company of women, but a place where they could partake in both. Around 1914, Louis ditched his meatpacking job, moved to Zeigler with Anna and little Jimmy, and there opened a boardinghouse that also served as a tavern and brothel.

Around this time, in 1916, a third family joined the picture when Leonard and Marie’s daughter Josie Krokvica married Steve Walko. He had also immigrated from Austria-Hungary, at the age of 16, and went to East St. Louis for work in the meatpacking houses. But after marrying Josie, he soon had another job opportunity.

The Zeigler boardinghouse operation apparently had jobs for everyone. By 1918 or so, Zeigler was the home to Louis, Anna, and James Kalish, plus Steve and Josie Walko and their two boys Ed and Steve, plus Anna’s parents Leonard and Marie Krokvica.

In 1920, Prohibition went into effect, banning the sale of alcohol in the United States. Demand for so-called bootleg liquor remained as strong as ever, so the national ban may have been a godsend for the family operation in Zeigler. The law was not repealed until 1933.

We don’t know whether Jimmy Kalish liked Zeigler, but we do know he liked going to school. In 1921 he received an award for perfect attendance at the Zeigler elementary school.

Also in 1921, over in Europe, Stefan and Kata decided to emigrate to the U.S. for a second time with their daughter Mildred. The hardships of living in a war-torn country were apparently too much to bear. They might also have received word of how much money their sons were making in Zeigler.

Sadly, somewhere over the Atlantic, Kata contracted pneumonia. A few weeks after arriving back in East St. Louis, it led to her death at age 52. Stefan Kalish then returned to Europe for good. Daughter Mildred stayed behind and moved in with siblings.

Louis earned enough money in Zeigler—from renting rooms, selling bootleg alcohol, and whatever else—that he decided at some point to start a similar operation in downtown East St. Louis. So he moved back with Anna and James around 1921, leaving Steve and Josie Walko to run the operation in Zeigler. Their daughter Dorothy was born in Zeigler in 1924.

In 1922, Louis Kalish made an astonishing investment in his East St. Louis operation. That’s when he paid $52,000—more than $900,000 in today’s money—for the Savoy Hotel at 201 Missouri Avenue. Located at the intersection with 2nd Street, it was a short walk from the Relay Depot, the city’s primary passenger train terminal. Although named for the luxury Savoy Hotel in London, its clientele was of a rather different sort. And it was located in the right part of town, a red-light district known as The Valley.

In the late 1800s East St. Louis began raising its streets to protect it when the Mississippi River flooded. In 1903, the city found itself under 39 feet of water during one of the worst floods ever recorded. The area around 2nd and 3rd Streets, between Missouri and St. Louis Avenue, had not yet been raised, so floodwater collected there as in a valley. The metaphor stuck.

Many property owners in the Valley simply walked away from their ruined houses and buildings on muddy streets. Tavern owners and prostitutes then took over.

Back in East St. Louis, the once penniless immigrant Louis Kalish was doing extremely well, running the Savoy Hotel and living there with Anna and Jimmy. The ground-floor tavern became a speakeasy, and there were plenty of rooms upstairs for both family members and the working ladies.

Louis had a reputation for generosity toward his patrons, loaning them money and not always getting it back. One borrower, unable to repay a debt, signed over the deed to an undeveloped lot of land on Lake Drive.

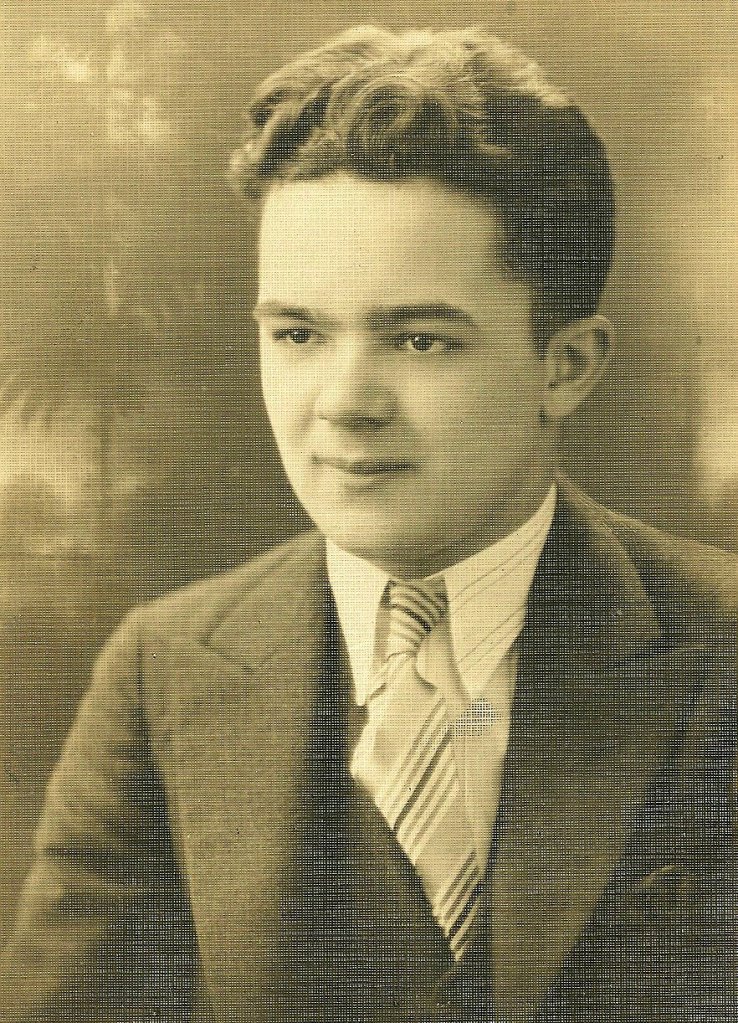

Jimmy Kalish continued to excel as a model student in East St. Louis, with two more years of perfect attendance. This child of saloon keepers was enamored with education and learning, especially history. At some point, he decided to make a career of it, telling his parents he would one day be a history professor.

His vision of his future self was in stark contrast to what he saw in his father at the time. Louis Kalish had not handled his elevated position well—this Louis was no saint. He was an alcoholic with unlimited access to liquor. Occasionally he terrorized his wife and son at home, forcing Anna and Jimmy to hide beneath the stairs as he trashed the house with a gun in his hand, vowing to kill them both.

The terror ended in 1926 when Louis Kalish died of cirrhosis of the liver. Jimmy had just finished the eighth grade. Then, only months later, his mother became seriously ill, of what we don’t know, and traveled to the prestigious Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for treatment. It didn’t help. She came home in worse condition and soon died.

In 1927, fifteen-year-old Jimmy was now an orphan. But he was not homeless.

After the back-to-back deaths of Louis and Anna, Steve and Josie Walko left Zeigler and returned to East St. Louis to help run the Savoy Hotel with Joe Kalish and other family members. With the money they had made in Zeigler, the Walkos built a nice brick house at 1324 North Park Drive, across from Jones Park.

The Walkos took in their nephew Jimmy Kalish, giving him a home across the street from a park with a natural swimming pool so large that lifeguards patrolled in rowboats, plus a quarter-mile track and baseball fields. Jimmy took full advantage of the park, dedicating himself to physical fitness, a dedication he would continue the rest of his life.

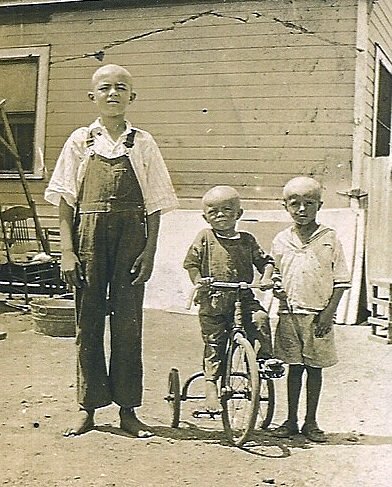

After losing both his parents, a teen-aged Jimmy Kalish was living in a nice house with a park across the street, surrounded by family. He was close to his cousin Frank Kavalier, son of his aunt Mary; Charlie Stengel, son of his Aunt Annie; and his cousin Louis, son of his uncle Mike. Life was good.

Unfortunately, within two short years after losing his parents, luck would turn again on Jimmy in 1929—and not for the reason you might think. Most people who lost everything in 1929 could blame the stock market crash that led to the Great Depression. Steve Walko’s family had only a very bad wager to blame. Steve lost every penny—and his house—betting on a pack of ponies at an East St. Louis track. He also lost his job.

With no house and no money, the six-member household—Steve and Josie, their three kids, and 17-year-old James—moved into the Savoy Hotel. It still belonged to Jimmy and continued to prosper as a brothel and Prohibition speakeasy.

The three-story hotel had 33 rooms, and Josie cleaned them all. With paying customers in every room, the family lived in a two-room space on the first floor with no kitchen. How they prepared meals is anyone’s guess.

Jim Kalish did not like living at the Savoy. But he remained stoic and focused on his studies, convinced that education would get him out of this place he didn’t want to be.

He excelled at East Side High School and continued his fitness regimen, soon able to do 100 push-ups without breaking a sweat. He did them every night before going to sleep.

After graduating high school in 1930, Jim attended college classes at Washington University in St. Louis. Then he transferred to Northeast Missouri State Teachers College in Kirksville. He had money for tuition, but not transportation. Fortunately, he knew his way around East St. Louis railroads, and hopped freight trains to get to Kirksville and back.

As a hard-working student, now at a teaching college, Jim Kalish was well on his way to realizing his dream of being a history professor. He loved college.

In 1933, on one of his visits home to East St. Louis, he met a delicate young woman named Bernice Malec at a dance. They hit it off.

Then, a few months later, Jim learned Bernice was expecting his child. He had a huge decision to make. Apparently, he made it very quickly.

As much as he valued education, Jim Kalish valued commitment to family even more. So he gave up his dreams of a college degree and teaching career, left Kirksville for good, and got a job hauling salt at the Swift meatpacking operation in East St. Louis.

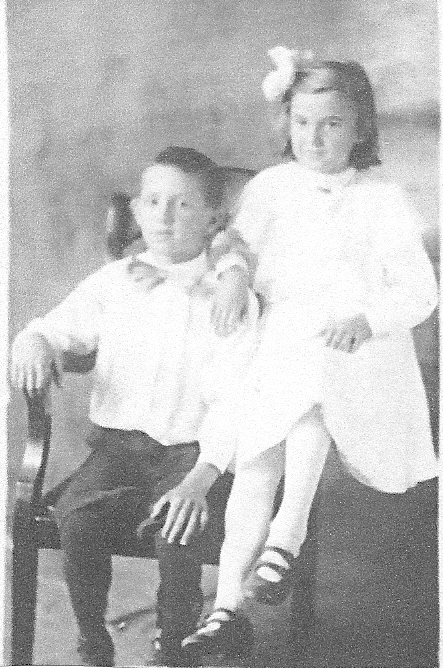

At their wedding in 1933, Charlie Stengel was best man. Bernice’s sister Angie was maid of honor. The married couple moved into a room at the Savoy. That’s where they were living when their daughter Lorraine was born in December 1933.

Bernice Malec was the youngest of six children of Adam and Julia Malec. Adam and Julia, just like James’s parents, had immigrated from Austria-Hungary—in an area now part of Poland—in the early 1900s, finding work in the meatpacking houses of East St. Louis.

As one might expect, Adam and Julia Malec didn’t like the idea of their daughter and granddaughter living in a brothel—especially when they learned another grandchild was on the way. They lived in a house they owned at 1117 8th Street, and a small rental house next door. It was vacant.

Shortly after Lorraine’s sister Jackie was born in 1935, Jim and Bernice moved their young family into 1119 8th Street. Jim and Bernice slept in a rollaway in the kitchen, and Lorraine and Jackie shared the bedroom. And that was the entire house.

The family did have a car. To give Bernice breaks from childcare, James would take the girls along when running errands, including trips to the Savoy Hotel to collect money from his Uncle Joe—before he drank it.

On one of those trips, after dark, James locked the car and instructed the girls to wait. Soon came the beam of a flashlight, in the hands of an East St. Louis beat cop, who tapped on the glass and asked the little girls what they were doing.

“Who are you?” asked Jackie, all of five or six years old.

“I’m a policeman,” he said.

“Show me your badge!” she shot back.

And he did—just before Jim emerged from the Savoy, hurrying over to make sure everything was all right. The cop said it was—but instructed the young dad to never again bring his girls to the Valley.

In 1941, the family moved to a house Jim built himself, with the help of college friends, on weekends. It was located at 5607 Lake Drive on property he had inherited from his parents, across from Lake Park. He saved money on construction by using salvaged wood from demolished buildings in St. Louis.

This house featured indoor plumbing and a telephone, amenities they had not had on 8th Street.

In 1942, as the nation was just gearing up for war, Jim received a draft notice from the U.S. Navy, directing him to the Great Lakes Naval Station north of Chicago. He took a train there and checked in. After returning home, he received a letter excusing him from military service due to his job in the meatpacking industry, which was considered essential for supporting the war effort.

Not long after his brush with military service, Jim left his laborer’s job at Swift and took a better-paying job as a clerk at the St. Louis Independent Packing Company, maker of Mayrose Meats, across the Mississippi River. This required him to take a bus to work. Occasionally, after an overtime shift, Bernice would put daughters Lorraine and Jackie into the family car, a 1940 Plymouth, and go to pick him up from Mayrose.

In 1943, Bernice gave birth to their son James Robert Kalish. For the 31-year-old Jim Kalish, life up to this point had been pretty rough more often than not. Now, at long last—living in a house on Lake Drive, with a beautiful young family and a decent job—life was pretty good. And it would stay that way.

The rollercoaster era of his life was over.

In 1952, Lorraine Kalish married Bill Durbin. They would have ten kids. Jackie Kalish married Richard Mahoney in 1954 and would go on to have four kids. The younger Jim Kalish married Ladonna Galoway in 1968. They would have five kids, bringing the number of grandkids to 19.

Jim Kalish was laid off from Mayrose at some point and then found work as a night watchman at a shoe factory. Bernice was unhappy with that job because it required him to carry a gun. After that job he drove a delivery truck for a flower shop. He would work until retiring in 1982 at age 70.

And he kept doing those 100 push-ups, every night, into his 80s when his doctor told him to stop.

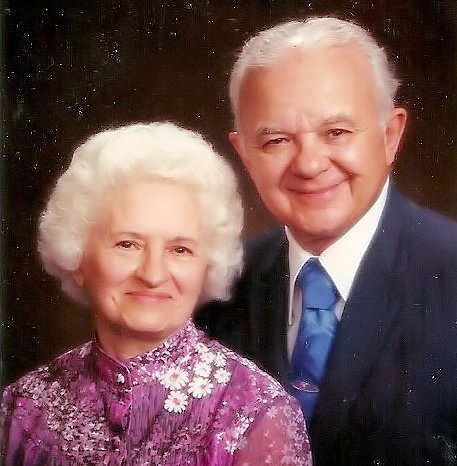

In the 1970s Jim and Bernice moved out of East St. Louis to nearby Belleville, Illinois. They were regular visitors at family gatherings at the nearby Durbin, Mahoney, or Kalish homes.

Many of us grandkids recall Grandma and Grandpa Kalish arriving in a modest sedan, with James in the driver’s seat and the passenger seat empty. Bernice sat in back because James, safety-conscious in all things, refused to turn the key until anyone riding up front put on their seat belt or moved to the back. Bernice chose the back.

Something else we all remember about Grandpa Kalish is how he tied his tie—very short, barely halfway down his chest. He knew it was not how other men wore their ties, but he said he just liked it that way.

Jim and Bernice celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1983. And in 1992, more than 60 family members gathered to celebrate Jim Kalish’s 80th birthday.

In 2002, Truman State University (as Northeast Missouri State Teachers College was then called) awarded James a certificate recognizing a life of encouraging education for his children and grandchildren. He and Bernice and all three of their children gathered at Fisher’s Restaurant in Belleville—a favorite—to celebrate.

Bernice Kalish died in September 2004, at age 90. She had lived long enough, she told her family, so she stopped taking her medicines and let nature take its course.

Our Grandpa James Kalish died in October 2008 at age 96. A few months earlier, he had developed gangrene in his feet. This was a setback from which there was no recovery. Both of his legs had to be amputated.

At his memorial service, everyone had a chance to look back and reflect on Grandpa’s life. His daughter Jackie brought a pair of her dad’s shoes to the service, placing them at the foot of his casket as she began her eulogy. And then she shared an especially fitting and poignant recollection. One time, as a teenager, she complained to her parents about not having something her friends had—a piece of clothing, maybe, or jewelry.

Her dad replied by telling her to consider a piece of old wisdom he had read as a young man and never forgotten.

“I once cried for having no shoes,” he recited to his teenage daughter, “until I met a man who had no feet.”

Our Grandpa Kalish left an impression on his grandkids we could not appreciate until we ourselves grew up. And then it became clear: Very few people have walked the face of this earth with the resilience and decency of James Louis Kalish.

This was a guy who went from hiding under the stairs with his mom in the 1920s, as an intoxicated dad trashed their house with a gun in his hand, to watching with eye-watering pride as one grandchild after another finished college, or managed a paper route, or simply walked into a room.

Thinking of him inspires me, by reminding me of the power of simply choosing to bounce back when life doesn’t go right—and to appreciate when it does.

Special thanks to Lorraine Durbin, Jackie Mahoney, Jim Kalish Jr, Ann Mahoney, and Beth Mahoney for their invaluable help in preparing this essay. There is more about our family history at https://michaeldurbin.com/familyhistory/

You did a great job of researching for this post. I also have found great stories of my relatives long after their passing, that I wish I had known while they were alive.

Dear Michael,

Thank you for sending this memoir. I believe I’ve read it earlier; some details sparked memories. But I read it this time with fresh delight. As always, your family history astonishes me (you can’t make this stuff up!) and your narrative tone carries me happily forward.

as added treat, the family portraits are so compelling and, given what we know about their hard-working lives, surprisingly elegant.

Peter